We have to switch off oil and gas. Renewables are cheaper and better and will stop us destroying our only planet.

..I'm sorry, you want more from this episode of Unsee The Future? ..Really?

Eesh, well. I mean, what more is there to say?

..Really, you don't just get that one point? That sums it all up?

>pooof…<

Well, okay. I suppose there might be a tad more too it than that, but really, if you have things to do you could run with the headline and skip the rest and… okay.

In this episode of Unsee The Future, I'll be looking at what it will take to power the human-planet future. The component part of our complete plan that will light up all the others, as it were. Or certainly enable them. Without energy, the modern world goes out overnight – and half the world has an emotional breakdown realising there is no more 24/7 human contact through eyes-decicating blue light and arthrihtic thumbs… only outside. And the neighbours. And you're worried about sea level rises.

As well as right here, you can listen on Soundcloud, Mixcloud or in a search on your favourite podcast app.

While shortages of everything seem to feed the fears of many future predictions, some today are talking of abundance. And while others of us today can’t afford to put the heating on or cook dinner, the big energy companies seem to be still making squillions in profits, while also nursing their own existential worries. And all while streets clog with life-shortening fumes and the atmosphere everywhere begins to warm enough to change the balance of life on Earth.

How do we eradicate fuel poverty while rolling back from the carbon red lines around the world? And just how can we practically feed civilisation’s voratious appetite for energy without burning everything we have?

The question we face together is: What price power? All depends what we really value – and yes, how we charge the chargecard.

CRANK HANDLE.

It’s all a wind-up. The climate crisis, the Green lobby, clean future energy. Well, I for one wish it was. When Trevor Bayliss invented his wind up radio in the early nineties, I think we all imagined the future would be clockwork. But if it really was the beginning of a ‘personal gen’ revolution, based on some brilliantly un-masstransmitional thinking, it didn’t translate into devices all around us being crank-driven and energy tarrif-free quite like we hoped. And that’s because a sensibly-sized geared tortion spring can only store so much energy. Imagine scaling up a clockwork car to Sainsbury’s run size and walking past a fully wound one in the car park – that amount of tension relying on No Sudden Explosive Brake Failure would give anyone a nervous headache. Be like Tina’s daughter’s wedding all over again. Would be a good work-out recranking the thing every half a mile, mind. As you watched bikes zipping past.

But, as Bayliss Brands explain, its eponymous founder did spawn a quiet revolution in ways to create microgeneration in tricky parts of the world, inspired as he was by a documentary on the spread of AIDS in Africa in 1991. Getting simple things like radios and torches working without plumbed political or constant-cost battery power supply would simply make hard living very slightly easier. And he went on to spend so much time developing the technology for his African markets he got to present a radio to Nelson Mandella himself. It’s an oddly poignient image, Treveor Baliss with Nelson Mandela, holding a wind up radio together.

In fact, the thinking has spawned so many other products today, that there is a burgeoning market world wide for personal-scale micro generation in lots of forms – from wind-up battery chargers, to kinetic power cells to micro solar arrays and gravity power and, well, so many things you can crank to life while traveling or camping, as Wind-Up Battery.com can help you explore better than the back pages of a Sunday supplement mag.

But in domestic life, our attitude to energy is rather different from the savvy trail riding of backpacking or far-flung field work. We take it for granted. Energy seems to us in the modern world like a commodity that just flows out of taps and sockets and accelerator pedals dependably – but the truth is, harnessing it is at least as tricky as generating it predictably in the first place. If the power goes out at home, you would not want to be sailing a kite in a thunderstorm to try to charge your iPhone X.

Now, before you say it, there is a difference between energy and power. You paid attention in Physics, but most of us have forgotten how things actually work. Energy is the capacity to do work, while power is the rate at which energy is used doing it. Energy is measured in Joules and power in Watts and 1 x watt = 1 x joule of energy per second converted into power. So two mighty watts of raw sound majesty uses two joules a second to play your dad’s Aerosmith compilation reedily through your budget bluetooth iPod speaker. In that way you do just to annoy him. Which means your budget bluetooth speaker had better be able to store a good 5,000 joules of energy if you are to get to Lightning Strikes from the reissued Greatest Hits before it conks out.

Electrical energy to power your dad’s classic Technics hifi in the lounge, and to recharge your budget bluetooth speaker, has traditionally come from dirty great power stations dotted around the country, transmitted expensively across leafy dale and wild moor to reach the substation at the end of your street through a massive infrastructure of cables, pylons and No Kite Flying signs, looked after in the UK by the National Grid. Energy generation, distribution and transformation that for years has started with burning sheer tons of coal or natural gas or by splitting atoms of Uranium 238 and 235 into gigantically radioactive fission reactions, all to turn tons of water into tons steam to turn turbines to turn generators to turn your lights on and your dad’s amp up to eleven.

These days, the country is typical of reasonably infrastructurally robust nations by having a mix of types of energy generation to keep everyone’s lights, air guitar parties and dialysis machines running without interruption. According to Energy UK, the 2018 mix of energy sources for my home country is split between fossil fuels, nuclear and renewables, with some imports from other countries. Those pipelines we imagined we were depending on Putin for rather worryingly.

Well, the current proportions of those fuels today are interesting to note. In 2016, according to their figures, 42% of the UK’s power came from burning natural gas, and 9% from coal. 21% of our energy here is nuclear, while renewables, including wind, wave, marine, hydro, biomass and solar made up 24.5% in the same period – and today is generally a third of all Britain’s power. And while we’ve been net importers of power in recent years, our imports come from dedicated supply networks with France, The Netherlands and Ireland, and it’s designed to regulate capacity between us as neighbours in both directions and we export much to them as well. So no nafarious global power players quite have the UK’s off switch on their desk yet.

The headline there is, of course – crikey Charlie, green energy, man. And as Utility Week reports, a new report suggests: “Renewable energy will account for more than half of the UK’s power supply by 2026”. But. Can renewables really save us from the warming of our atmosphere that is the inevitable and measurable effect of so many fossil fuel power generation plants and factories burning all day and night? Or are there problems with rolling out the green alternative?

There are problems. Not least of which, resistance. And crossed wires.

BATTERY PACK.

Australia. It’s been hot, lately. I know, you look up from cupping your tepid chai latte and then dispondently out of the rain speckled window you are sitting photogenically close to and give a shivery sigh of seasonally affected “whatever.” But for many Ozos, it’s not been all Christmas turkey on the beach and Olympic volleyball practice. Temperatures hitting the forties have returned this year, putting a strain on many aspects of health, infrastructure and wildlife, and highlighting one particular problem the country is labouring under all year round. An energy crisis.

More than a year ago from when I write, in September 2016 down under temperatures soared… and the lights went out. A rolling blackout across South Australia put thousands of families in the dark for the evening and many more for more than 24 hours. Virtually the entire state was knocked out from tea time and metropolitan Adelaide only came back online by ten pm. Bit of a bugger, to say the least. But warnings of more ‘load shedding’ blackouts were issued at the time for wider Australia, including New South Wales.

As News.com Australia reported, SA’s Energy Minister Tom Koutsantonis said then: “The problem that is occurring here is coming to a city near you on the eastern sea board soon”.

Doesn’t sound like a very robust modern bit of infrastructure going on there, does it. Or bon homme between neighbour states. And the problem hasn’t gone away since then. So what is the Australian power problem?

Mr Koutsantonis supposedly put is bluntly: “A massive catastrophic failure of the national electricity market.” Ah. Well that’s good to be clear on.

“There is a problem of generation and the way the market operates in this country,” Charis Chang reported him as saying. “That is, we have an oversupply of generation, yet the market is unable to dispatch that electricity to sufficiently meet our needs.”

Nine months later a remarkable open letter to the country’s government, signed by an interesting cross section of business, basically demanded a resolution to the ongoing crisis. Not yet sorted out. In an interview with ABC News in October last year Innes Willox of the Australian Industry Group, one of the signatories, says: “Autralia should be an energy superpower. We should be the nation the rest of the world looks on with jealousy”.

He estimated that Australian energy bills over the last couple of years had seen at least a 170% increase which, as he puts it: “For many businesses this is just not sustainable.” And, by all accounts, simply many households, with increasing numbers of people reported sliding into health-threatening fuel poverty around the nation.

The blame for blackouts and clog-ups in the market was laid by some loud voices at the foot of renewable energy.

Coal and gas have driven Australia’s power for decades, of course, but forcasted demand for power in the country hasn’t panned out quite as imagined in recent years – falling, in fact. Partly simple economic flatlining but also significantly because of the uptake of domestic solar power. Also in play is the RET – the Renewable Energy Target. A subsidy to bolster greener energy systems that’s supposedly supported by both major political parties in Australia, in the country’s stated climate crisis commitments. Problem is that the shortfall in general energy demand has meant that renewables haven’t so much made up the difference in power needs but begun to push old power out of the picture.

As ABC News reports, add to this the fact that the country’s fleet of coal power stations is retiring almost en masse, and that the gas production of Australia seems to be heavily contractually tied up with exports, rather than domestic electricity production, and you have a system simply not delivering reliably to ordinary homes and businesses.

South Australia has a significant percentage of wind energy in its base supply mix, which you can see in jolly live data on SA.GOV.AU’s fact page. Just looking at this live snapshot, you can see that of it’s comparatively modest almost 1100 megawatt usage, some 210MW are made by windfarms, with 870 of it coming from gas. But that doesn’t cover it entirely, as it has a degree of battery power feeding the grid as well – and, according to the government, over 20,000 homes now generating their own PV power. Rooftop solar.

You should see New South Wales and Queensland by comparison. More than 8,600MW and 6,300MW respectively of dirty coal energy being used at half ten at night as I watch the graphs flicker. A modest squirt of hydro and wind top up NSW with nothing renewable visible at all on QL’s bar. Strike a light, mate. And that’s just an average Thursday night at the back end of summer.

South Australia’s public dependence on wind marked it out for blame when the first black-outs hit. The accusation was, the capricious nature of renewable windy-blowy who-knowsy-when-it-willy couldn’t regulate demand in a crisis.

Well – no, actually. Turns out, those particular major blackouts happened because of a freak-scale storm that brought down distribution infrastructure – bent pylons – that effectively tripped out a system that couldn’t regulate wider flow because of a combination of an ailing network and market politics. In the rows about it in the days afterwards, the conservative Liberal government treasurer Scott Morrison actually broke the parliamentary No Props, Puppets Or Puppies In Your Show rule and waved a lump of coal around the dispatch box, telling people not to be scared of it. Well, Scott, voters can be funny buggers, sometimes scared of technology – though, if pushed, I would personally rather place my fears in the blackened hands of lungs-destroying nineteenth century technology.

Now, while this was a weirdly obtuse willy waggle at the oppostition, the Labour party in Oz may talk of the need to increase green energy across the country but they actually reportedly push with less conviction than it might seem, tied as they are to unions that rely heavily on coal jobs. Hmmm. So it sounds like there is very little appetite for renewably futury energy technology amongst the ordinary Australian electorate. Especially at the moment.

Enter two billionaire wundertechers in a very public Twitter exchange about the issue.

When Elon Musk tweeted thoughts about the potential of modern battery power to save Australia’s supply problems, Mike Cannon-Brookes called him out on a claim that he could “Solve SA’s supply problems in 100 days”.

“How serious are you?” he asked. “If I can make the $ happen (& politics), can you guarrantee the 100MW in 100 days?”

Musk replied that he’d supply it free if they hadn’t got it done in time. Then when to check with his team they really could.

The result is the world’s biggest battery project, just outside Janestown in South Australia. 100MW, driven by wind. Just done. But that wasn’t all. It showed the appetite in Australia for new energy thinking, as 60 minutes reported at the end of October.

Having called out Musk, Cannon-Brookes apparently did some catch-up homework on renewables generally and discovered much more support than he expected.

“I got multiple unsolicited offers,” he told the programme. “I think we added it up to a hundred million dollars in offers that came in. It was amazing. It was inspiring. As an Australian. To see people wanting to solve these problems in a real and meaningful way and I think they’re just sick of the politics on all sides.”

Scott Morrison was, on behalf of the government, mocking. “Have the world’s biggest battery, have the world’s biggest banana” he said. There’s another prop he could sneak into parliament.

Environmental writer Tim Hollo, on the other hand, told The Real News that the Tesla 100MW battery was “Just one of many game changers we’re seeing coming one after the other at the moment around the world in the development of renewable energy.”

When asked: “Are the coal companies floundering?” he replied: “Yes. The really big problem that they have is that renewable energy lends itself to decentralisation and therefore to democratisation of the energy grid.”

Hugely profitable control, as he calls it, gets harder to maintain, in other words.

In a Guardian article he refers to the Climate Institute’s Climate of the nation 2017 report which showed that over 70% of Australians are actively pro renewables. As he summarised, the report showed that: “..the vast majority of Australians want to see more renewable energy, do not believe that renewable energy is driving price rises (correctly identifying mis-regulation, privatisation and other corporate price-gouging as more to blame), and don’t think renewables need fossil fuels to back them up in the long term.”

Ah. Interesting.

The practical truth is that around the world coal is a dying industry. Been doing so for decades, of course, with investors in the technology today disappearing like choking swallows near a Rotterdam refinery fire. Natural gas is still a big player to keep the lights on but is still fundamentally a leaky, flammable fossil fuel. Making nuclear, for many people, the most viable heavy lifting contender to get us going greener. Despite slight hickups like Fukushima in 2011, which suffered a power outage to its plant cooling generators after the tsunami on the 11th March which, as the Wikipedia page puts it: “..led to three nuclear meltdowns, hydrogen-air explosions, and the release of radioactive material in Units 1, 2, and 3 for four days” and more. Oh, and the cordoning off of half of Ukraine for 30 years after the Chernobyl emergency training proceedure that went a little off course in 1986. The only two Level 7s on the International Nuclear Event scale, disaster pub quizz fans. Let’s not even mention whether there was or wasn’t a ‘secret’ recent event elsewhere in Russia causing alleged radition level 1,000 times the norm over there somewhere or other. Shhh.

The point is that Nuclear is getting old. Like elsewhere, the UK’s once-groundbreaking atomic powerstations are getting to the end of their working lives, with as Energy UK says, “all but one expected to stop running by 2025”. Replacing them might simply turn out to be prohibatively expensive today.

So what is the state of the world’s challenge with any kind of new energy, then?

METER READING.

The Global Goal for energy aims to: “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

Its targets include trying to ensure universal access to modern energy, trying to increase the share of renewable energy in the global mix ‘substantially’ while doubling energy efficiency outputs, while generally trying to get all countries upgraded to more sustainable power infrastructure.

As it says in its opening statement: “Renewable energy solutions are becoming cheaper, more reliable and more efficient every day. Our current reliance on fossil fuels is unsustainable and harmful to the planet, which is why we have to change the way we produce and consume energy. Implementing these new energy solutions as fast as possible is essential to counter climate change, one of the biggest threats to our own survival.”

Which is all fairly epically hopey-changey and a little woolly. What are the actual possibilities?

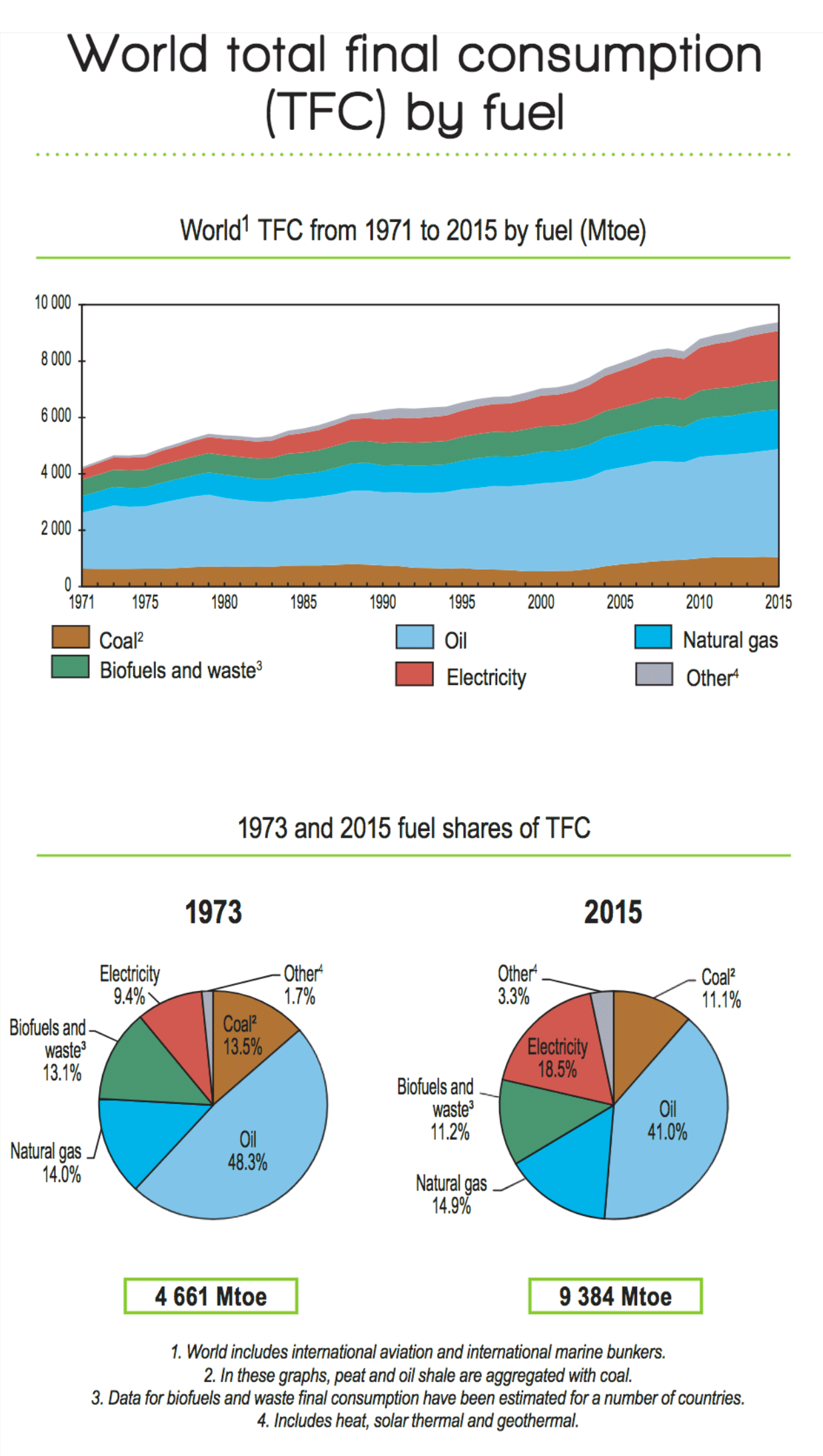

I’ll just bet you want to get into some epically incomprehensible figures first to go with it, right? Well, if you want headlines, the International Energy Agency’s Key World Energy Statistics report for 2017 has some handy graphs and pie charts you could chew over nicely for a bit, but it shows up front overall planetary energy supply has gone from 6,101 million tons of oil equivalent – or Mtoe, which sounds like an unpleasant wardrobe malfunction to me – to over thirteen and a half Mtoe by 2015. In 1973, oil formed nearly half of all of that directly, it being the most equivalent thing to oil there is, with coal making up virtually a quarter and natural gas 16%. Surprisingly, biofuels and waste made up more than ten percent. Hydro power was double that of still fledgling nuclear which barely makes it discernably to the pie chart at 0.9%. But by the middle of this decade, not only had total global power production more than doubled, the mix had changed weirdly. Less oil, down to 31.7%, but more coal, at 28.1%. Nuclear had grown to almost five percent of all global energy supply, but biofuels, for all the talk of a brief revolution in putting plant oil into cars ten years ago, had reduced to less than ten percent.

By far the biggest regional growth in the energy market was Asia, in sheer volume as well as percentage – gone from less than thirty percent of the world’s power consumption to all but half today. Europe was the biggest user of power back when I was a toddler but today it’s actually contracted as a market, As have the americas, interestingly.

Greener sounding power like solar and hyrdro has been massively the preserve of your OECD countries – ‘developed’ nations.

Interestingly, according to these figures, we used rather less power than we produced, as a planet. A good 2,000Mtoes in 1973 and over three and a half thousand Mtoes in 2015. That’s a lot of over supply. Especially when you consider how dirty most of that energy is – and oil for road makes up essentially half of all total oil consumption, which stands at 3,8040Mtoe. That is a LOT of dirty, burn it once fuel for getting about in cars, lorries and road public transport. Might want to note this mentally for later.

I really should try to translate all units of energy and power – Joules, terraWatts, Mtoes – into the more modern universal metric of the kiloWatthour, the kWh, so that we can begin to stand a chance of understanding the equivalents of value going on here. And also so I never have to say the word Mtoe ever again.

But whatever the units, where are renewables relatively in the mix today?

According to the same report, hydro has more than tripled in four decades, wind energy increased by a factor of eight and solar has ballooned by more than SIX THOUSAND PERCENT. But that’s hardly surprising as solar energy technology in 1973 was little more than a shiny tin lid to cook street food on in rural desert country. And anyway, all of this growth still represents a small fraction of what we actually need.

REN21 has it’s own report dedicated to the renewables sector in 2015, as a handy companion, which has plenty to wade through on a cold February night with your thermostat turned right up. And it’s headline is simply that 78.4% of total final energy consumption globally was still fossil fuels, with nuclear contributing 2.3% of total – and combined renewables making up 19.3%, growing together at just over the rate of demand so far. It’s registering, but it’s hardly turning the tide.

Yet.

As Madeleine Cuff reported for GreenBiz in November, a different report form the International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2017 “..tells the story of an energy industry on the brink of a seismic shift, as it struggles to deal with the twin pressures of decarbonization and rising energy demand.”

GreenBiz summarises this more strategic report into ten headlines that open with the trend forcasts that both carbon emissions and energy consumption are only set to go up over this year – possibly looking at “another India and China” added to the consumption by 2040. Riiight… But while they consider coal’s days to be waning dramatically, with the US currently the biggest peddler of all fossil energy, China on the other hand is a world leader in green energy generation and facilitation and renewable energy is set to double by 2040, with electric vehicles dramatically helping to reduce the still serious global problem of pollution.

Many greens are hoping, Cuff says, that the IEA’s will turn out to be, as it often has been, a little pessimistic in the rollout and effect of renewable technology into the energy sector.

But, as a McKinsey Energy Insights report claims: “Despite the accelerated development of renewables, electrification across sectors, and efficiency developments, we expect 2050 energy-related CO2 emissions to be 1.5-2.0 times higher than the level necessary to meet the 2° Celsius target.” As they outline, despite electricity demand predicted to grow four times faster than all other fuels between now and 2050, and the dramatic cheapening of renewable tech, they imagine we’ll still be using a lot of fossil fuel and driving climate change thirty big years from now.

As a big global business consultant very used to working with the oil and gas industry, you might be tempted to cynically imagine, you old greeny, that McKinsey & Company would be a little generous in its interpretations of fossil fuel consumption predictions and optimistic in its CO2 level predictions. But the tone of their report is flatly inclusive of all energy sectors and concludes with the essential challenge that we are currently on course one way or another to be about half way through our great energy revolution opportunity when the world finally catches fire. ..I think I may be interpreting a little there.

Less dramatically, Utility Week‘s article on the BNEF report appears to grasp the nettle in many critical thinker’s minds when it says of the UK’s energy trends: “By 2040, almost two thirds (63 per cent) of power will be generated from renewable sources… and at “certain times” wind and solar energy alone could meet total power demand in both the UK and Germany” but that “at other times, there will be “entire weeks and months” where solar and wind will produce “little energy”.”

Base Load, mate. It’s the hefty controlable wallop we need constantly to regulate national energy demands. And renewables just don’t work like a power plant.

The late, brilliant, Sir David MacKay gave a TEDx talk back in 2012 from principles in his influential book Sustainable Energy – without the hot air. He was good at helping people focus on the real numbers involved in our energy needs.

“One coal-fired power station equals 2,000 wind turbines,” he said to Leo Hickman of the Guardian when the book was published almost ten years ago. “When we retire a technology, we must know we have made the right choice.”

What will it take to really make up our power needs with cleaner alternatives? Numbers, facts, universal power terms, he says. But such clarity seemed to be his main agenda, not politics. As he says in his talk, quoted from the book and by everyone who’s met him since, I suspect: “For the record I am not pro-nuclear or anti-wind. I am simply pro-arithmetic.”

He uses the metric of watts per square meter to show density of power demands around the world, and the fact that renewables tend to need a lot of land to add up to the output of concentrated power plants. In other words, as he said back then in his 2012 talk, where will we put all the wind turbines and solar panels we will need to get our huge output?

He concludes that all we have to work with when ‘people hate everything’ – both worthy green and dirty fossil – is numbers. And that to make the numbers add up, we will have to combine a lot of different elements at once. But, he implies, it’s not just worth a shot. It’s worth everything to try.

SEEING THE HOPEY-CHANGEY BIT.

My longest-standing close mate Mike is very useful for a getting different perspective on things. He might be essential to any team planning something, because he is likely to have a thoughtfully incredulous alternative take on whatever hype you are enthusiastically talking yourself into – which could be put to good use helpfully early on in whatever expensive process you are budgeting your way into. When you zag he’ll ask why you even want to use such hoary old marketing guff.

“Elon Musk” he said to me on our latest carousal around Southbourne’s pleasant social establishments on Friday night. “Takes the world’s greenest sports car and straps it to the world’s most expensively unenvironmental propulsion system in history.”

My smile dropped.

“And all to create another bit of space junk. Not even space junk that had a practical purpose to be in space in the first place” he added incredulously, upending the Malbec bottle into our glasses.

You see? Perspective.

He’s right to keep us looking at the reality of our cosy green endeavours. And he’s qualified enough to ask such awkward questions because he’s a journalist, he’s always been a curious techy tinkerer and he’s someone who knows only too well the hard work and planting savvy it takes to work with nature, working as he and Emma do an impressively productive allotment.

But the successful launch of the Falcon Heavy on that very morning was a bit of a wake up call to the world for what’s possible. And while the fan girls and boys of SpaceX and Tesla and Musk’s whole attitude were alway likely to woop the theatrical chutspah of Rocket Man, the truth is such theatre helps get attention. And that’s what’s needed right now – some dramatic new storytelling.

There is something happening around you today that is nothing less than a revolution. And encouraging it may be the Trojan horse of change, for it is the thing that may change your outlook, and so possibly the world’s during our lifetimes. The electrification of everything. It may be our greatest domestic hope.

Not simply because it is greener sounding to dishonest socialists like me who consider spending their money on their pompous public conscience, but because the nature of the technology as we will use it will begin to change how we see things. How we value things.

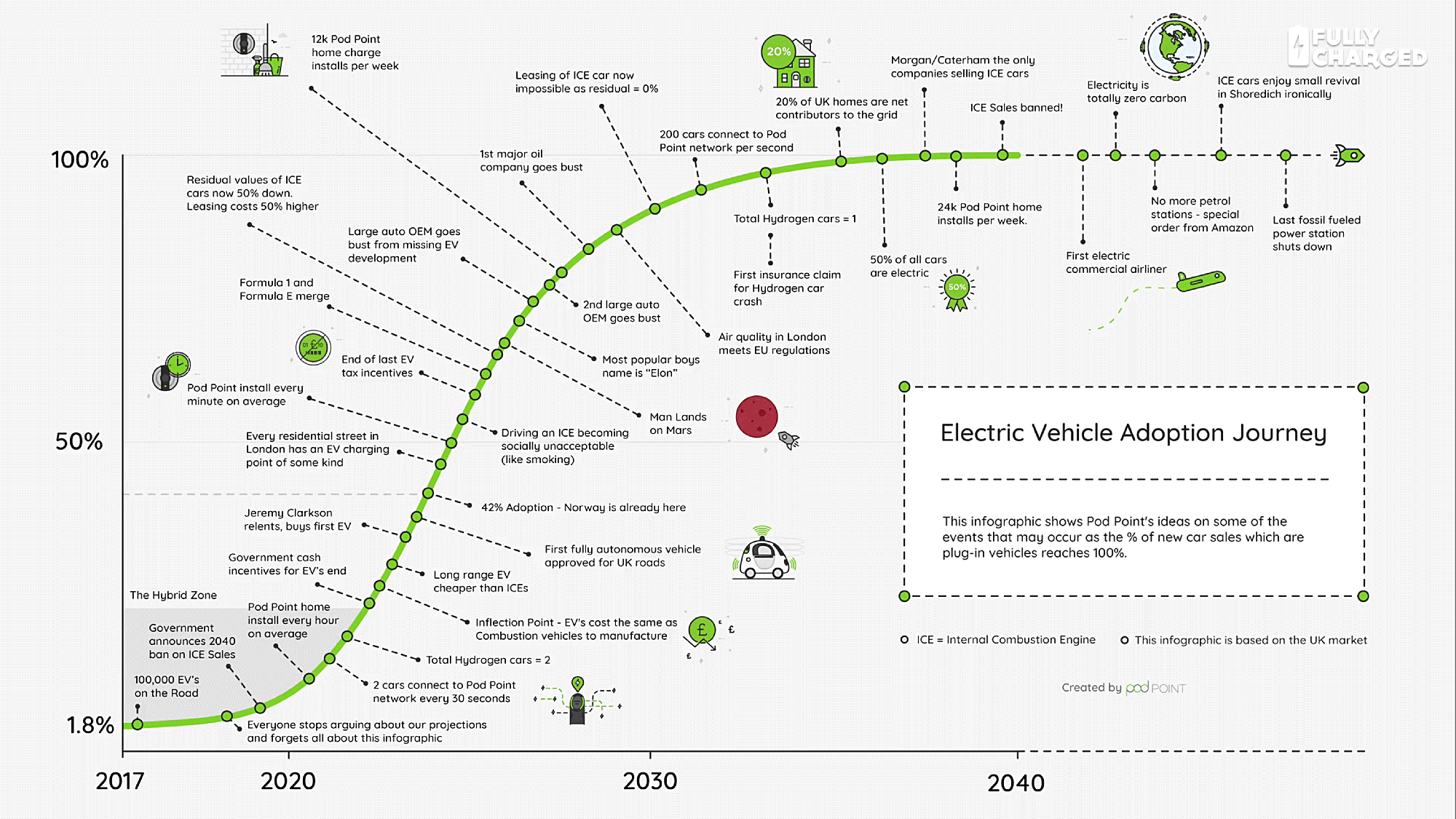

Erik Fairbairn of electric vehicle charging infrastructure company, Podpoint, gives a fascinating presentation to Robert Llewelin in his online EV channel, Fully Charged. And his starting point is that the UK government’s recently stated aims of all cars being electric by 2040 is rather less than ambitious. In fact may be an aim lagging way behind the technology.

Electric vehicles? I made a bet with an old friend of mine rashly over dinner after a decent couple of glasses of his Bordeaux back in the summer. A bet I am going to lose. But not by as much as my friend Ian currently imagines.

As a doctor and consultant, Ian is not only a bit of a wag he’s a solidly factual chap and so laughed with scornful derision right in my face when I said more cars than not will be electric in ten years time on British roads. I naturally swigged more of his wine in defiance and shot back: “I’ll bet you”. He said: “You’re on!” with an immediate snort of disbelieving opportunity, reaching across the table for my hand enthusiastically. I had the scraps of wherewithall to say: “ten pounds” before the flesh was pressed.

Bet you think similarly to him. EVs are a bit of a joke, right? Or are you just beginning to come round? You may be. But Erik Fairbairn’s little presentation may have you looking again at what you think you know about the coming revolution in automotive design.

This is one little bit of Unsee The Future that will definitely be amongst the swiftest to sound out of date, I imagine, so rapid may the pick up of EVs be in the coming two years alone. But currently, says Erik, there are five barriers to people actually committing to electric wheels instead of bang-pop push ones – cost, range, charging, choice and performance. But if these barriers get deconstructed, the road will be open to the EV.

Cost? Well, there’s no super-affordable mass-produced option on anyone’s forecourt currently. But the cheaper day to day cars like the hugely successful Nissan Leaf are comparable with other pretty boring small-to midsize runabouts, while BMW’s i3 and VW’s eGolf both tackle the kind of quality hot hatch price bracket. These options alone seem well within the monthly means of an awful lot of car leasing commitments across Europe and America. And the resoundingly successful and loved Tesla S at the £80,000 bit of the market may not seem like a car for the people but you see those suckers everywhere. I saw a whole fleet of them operating as taxis in Amsterdam.

Between them, actually, the Tesla S and the Nissan Leaf arguably changed the game. Because they made commercial success out of electric, in rather different price brackets – Tesla with imagination-grabbing showbiz and style, and Nissan with quiet, fussless useability. And this has helped people increasingly discover that performance really isn’t a problem – an electric motor delivers power instantly, like only a massive engine blocked V8 can without a turbo. Torque, mate – EVs can easily have seat-squeezing buckets of it.

Range anxiety is the biggest barrier facing the potential EV customer today, I think. Coupled with infrastructure concerns – finding sufficient charging points. But the truth of your average motor is of course that it spends most of the time sitting idle, or pottering just a few miles. Which means it doesn’t need much range between massive charges while it squats on your drive overnight or outside work all day. And as more cars coming onto the market increase ranges nearer to and above 200 miles, there is a sort of magical “Oh, okay” that drivers suddenly feel and figure this is fine. Rapid charging is turning up more and more in motorway service stations where you’ll need it, and this will top up your battery sufficiently enough in a wee and coffee break. If you ensure you always have coffee after your wee you’ll ensure you have to stop again in 200 miles – see? Integrated thinking is key to sustainable tech.

The real game changer will be choice. Because if you don’t get excited as a car geek about what all the majors have planned for the next couple of years, you haven’t been paying attention – the range of cars coming will give something for everyone. And in designs that will take the whole experience of driving and the class of design of cars forward in leaps not dragged out of a foetidly stagnant car market for decades.

And remember, the EV will be a lot cheaper to run. Right now, the cost of charging and using one seems to be about half that of petrol prices. A wildly broad figure but loosely enough to take in here. But there’s also the lack of vehicle tax here in the UK. Green car, innit? Then there is the significant reduction in maintainance. If you consider that the average petrol car has some 3,000 moving parts and the average EV has fifty… that’s a lot less to go wrong. We can talk about what my neighbour Jon will do for a job as a mechanic in 2050 another time – he’s not bothered, he feels he’s likely to have retired by the time we’re both 80 – the point here is: Cheaper To Run. Less To Go Wrong. And then there is the sliding graph of battery production getting cheaper even faster than predicted, rendering the EV significantly cheaper to buy in the coming years. Oh yeah. And no more kerbside poisoning of our children and grannies. Or adding to global warming through the tailpipe.

As Erik says simply: “It’s going to get to the point where you will have to have a seriously good reason to choose petrol.”

But Fairbairn’s real winning explaination is his sliding scale chart. And I can only say study it for a bit. It’s gently amusing and very enlightening – the take-up curve of EVs between now and 2040. Short headline is: That curve lifts fast.

They predict 42 percent of all new cars are electric by the mid 20s. But, as Erik points out, Norway is to that degree already and more. “By 2030,” he points out, “it will likely be impossible to lease a petrol car. Because the residual value on them will be so low, who are you going to sell it to afterwards?”

Crikey. I have to say that ever since I started looking into EVs – yes, with a mind to finally say goodbye to our old TDi and go the full family Sinclair C5 – I’ve walked past local used motor dealers and thought… oh. Hmm.

In 2018, you likely don’t get it. This sounds pipe-dreamy. In five to seven years time I think it will be obvious.

Does it matter that much? I think yes. Because EVs will score a lot of wins at once. They’ll address the air quality crisis directly. They’ll give users cheaper driving. And they may be the single most effective thing at actively engaging ordinary twerps like you and me with environmental thinking. We don’t ‘alf love our cars.

Now yes. Road haulage. A massive diesel problem. But it’s far from unlikely that battery and motor design will scale quickly to truck sizes. Tesla have already done it. And many bus companies have been running electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles for years. It can all add up. Germany even unveiled a test rig of a hydrogen train, to help get rid of the diesels on unelectrified lines.

It can all add up.

The single biggest travel problem that dwarfs all others is of course, air travel. And it’s why many models and commentators seem to think we can push to get a long way by 2030 – even 80% renewables globally if we really focussed – but that that last 20% will take another twenty years. Jet air travel is massively terrible for the environment, and there’s no quick fix for that kind of propulsion. But, hydrogen power is being played with seriously in this arena and electric light aircraft are just a thing now, scaling bit by bit.

The appetite to push is much more from certain business sectors and from many ordinary nobodies on the street, rather than politicians. The trick will be breaking the political cycle of “Hey nobody likes change or asks for green stuff, the Greens are just a bunch of dishonest socialists and deluded hippies, right guys?” to encourage more political voices to feel it’s a vote winner to push for green energy. But it can happen.

As Tim Hollo says in a Guardian article: “Often politics deals in ephemeral ideas, subjective ideas, ideas about how well off we are, how confident we might be about the future, how safe we feel. Decades of political focus on the dismal science of economics has enabled this. Politics can become a confidence game. But sometimes politics comes up hard against reality.” The Tesla mega battery event in Australia was just one such in renewables history. And it all chips away at the established thinking and political ruts.

What our sustainable future energy make-up will have to look like is much like all sustainable thinking – a quiet revolution in total outlook. Namely: Lots of small effects being consciously added together.

Firstly, as David MacKay said in his TEDx talk, we essentially have six big levers to pull around to manipulate our future energy sector – six options for making up the power we’ll need with dramatically less CO2 emmission: Our own renewables, other people’s renewables, nuclear power, more efficient transport, more efficient heating and insultion and… meter reading.

And this last one illustrates the point I am feeling is becoming fundamental to a hopeful, sustainable outlook for humans in everything. Knowing what’s actually going on. Metrics, in other word – live data, brought to us much more easily with modern technology, like apps and sensors. You may already be used to reading your smart meter, and it will, I am sure, have changed your energy consumption. With your meter no longer spinning it’s little wheel frantically in a cupboard under the stairs behind all your paint tins while you fall asleep on the sofa with the thermostat turned up, but displaying a few big numbers on your kitchen work top when you potter in to make tea, you are more conscious of what you are using. Of what you are doing.

“Reading my meter changed my life” said MacKay.

This is a significant cultural reason why EVs may help change the world. You have to drive them consciously. ..Admittedly, even this will change when AI takes the wheel in autonomous vehicles and you can actually have a nap on the drive to work. But the immediate point with beginning to use an electric vehicle is that you have to drive them aware of every mile, as you work out how far you can travel in a world not yet easily fully geared up to support you driving around with carefree entitlement wherever and whenever you please. It’s a technology built on energy awareness, knowing how much power the car uses and how long it takes to charge.

Just imagine integrating that with your household energy use. And your thermostat controls. And some IoT gubbins for your lighting and food consumption. And, why not, along with a little photovoltaic energy from the roof, buffered nicely in a house battery. You would have, after your intial investments, some domestically free energy to live and travel locally. But you’d also have a much better idea of what energy it takes to move your life around.

That’s going to transform your outlook, isn’t it? To not simply give you more affordable freedom, but a much greater sense of oddly empowered responsibility – awareness of the real value of things. Despite it being cheaper.

That kind of outlook can changes the world, I might suggest.

For me, the whole impending EV phenomenon is not really about cars. Much as it might actually make cars fun again. Erik Fairbairn says simply, while looking at his take-up curve of EVs: “You cold probably do another graph, a bit like this, talking about how we move from centralised energy generation today to decentralised energy generation” and he goes on to site emerging statistics that the cost of solar energy generation is getting cheaper now than the cost of simply distributing electrical energy from our big power stations to our homes. Just the distribution. So if you can build Hinckley Point for free and generate all its electricity for free you can begin to compete with the potential roll out of solar to every domestic home.

I know, I’m being obtuse. It’s also the emerging market reality. While I as PM would expect to keep large simply guages with flickering needles on my desk to know we always had GB’s lights on, it may turn out that we simply can’t afford to start again with Nuclear. That ship may be realistically sailing as we wave hankies on the dockside, contracts or no. At a time when national finances appear to be threadbaring apart many social fabrics that hold the nation together, tying us to a huge bill with France and China, to hand the global economic superpower another key chunk of sovereign infrastructure – to say nothing of a dastardly EU member state in a post B-word England – while also creating a single massive cyber security target… well, it seems a mis-strategy to me. In today’s world.

Something in my water is telling me we should use the impending energy crisis of decommissioning old power stations to ramp up a world-leading roll-out of renewables and energy efficiencies to the people. Like it’s a war campaign. Which it is. A conflict with our own destructive economic culture.

And where shall we put all those PV cells as we install for victory? I’d simply say, how many buildings have a roof?

Of the current £20billion cost of a new nuclear plant in Somerset, what if we scrapped it and took half for an aggressive investment in dissipating our energy demand to more localised networks of thinking, including some R&D to help rival Tesla’s development of the PV rooftile? And the futury potential of transparent PV – turning windows into microgen. I leave that there.

Of course, even with the momentum of the microgen market as its already unfolding, without a sudden fundamental cultural turn around from a Conservative UK government, or a toxically-minded US leadership, the next ten to fifteen years will be crucial. In overcoming the challenges as much as establishment cultures.

Jean Kumagai reported for engineering and science body IEEE’s Spectrum magazine back in 2014 of the ambition of Fort Collins, Colorado, to become a net-zero energy district. While her article’s standfirst lays out the engineering goal – “Smart and agile power systems will let every home and business generate, store, and share electricity” – she goes on to summarise one significant technical challenge in fundamentally changing technical demands: “Today, every time a homeowner installs photovoltaic panels on the roof and begins spinning the household electricity meter backward, every time a plug-in hybrid owner decides to charge up the car batteries, and every time a new wind turbine starts to turn, it perturbs the grid. Though those individual perturbations may be slight, as they begin numbering in the hundreds of thousands or even millions, the strain on a grid not designed to handle them will become potentially disastrous.”

The purpose of home generation in a sustainable context is not to adopt a middle of Montana idea of bunkering in and going off grid. It’s to change the grid into an exchange. An ebb and flow. A relationship between your car, your house and the national supply. Giving and taking. It’s a hell of a headache to adapt the big infrastructure to, but in the end it will create a much more robust national energy system – instead of a few massive single points of security and supply, the grid will be a dissipation of millions of tiny links. I can’t think of a more symbolic summation of a positive 21st century outlook.

That 60 Minutes‘s report on the Australian energy challenge captured a perfect penny-drop moment to illustrate the very obvious point about all this. It visited a couple who had agreed to trial one of Tesla’s house batteries with a solar array, Michael and Melissa Powney. They’d already had it installed before the great power cut of 2016 that knocked out 90,000 homes in SA. Melissa said this simply:

“I suppose I didn’t realise the impact of the power cut until we got home that night. I think we confused the neighbours because our lights were the only ones on in the street.”

We may as well remember in all this, it’s not like the culture of the oil and gas industry is winning over ordinary people beyond its paid staff. As widely reported in the UK autumn, the big six energy suppliers to the country made a profit of £1bn between them last year, increasing their market share in recent times “despite losing millions of customers to challenger firms” as Adam Vaughan puts it in a Guardian article. Playing the tarrifs confusion game, according to the Ofgem report that highlighted it. Where is the human mindedness in that kind of business model of future energy? Sounds like a fundamental part of the problem to me.

And why we need to push for a renewable future. It’s not simply the need to try to save a workably normal relationship with our planet’s environment, it is our opportunity to tackle the short circuit at the centre of modern human culture – the way we habitually ignore the true cost of powering our hopes. At home, at work, in industry. I suspect that changing our outlooks domestically will simply begin to infect our thinking in everything, as our generation evolves how we do even the biggest energy intensive things, like flying around the planet or manufacturing steel or… making cars.

Is it possible? Well, many businesses are banking on it, in an interesting natural mix of business intent and human intent. It’s the combined outlook that will save us. The not seeing a difference between them.

Boss of Good Energy, and sustainability champion Juliet Davenport, simply has this tweet pinned to the top of her page: “2018 Renewable wish list: @TidalLagoon – let’s go; @SolarPowerPort – on every roof; @Comm1nrg – for onshore wind; @GreenGasCert – no price cap; @REAssociation – battery in every home and business. Now that really could then keep us on track for 2018!”

The more they look into it and consider it and explore the possibilities, the more people there appear to be lit up by the idea of a truly progressive global energy system.

In a supremely symbolic note, it might be worth taking a final bit of inspiration from a small country no one’s really heard of. The tiny Kingdom of Bhutan. Less than 800,000 souls living in the remote Himalayas, all but disappearing between India and China. A place its prime minister, Tshering Tobgay, says has sometimes been called Shangri-La. But, he says, it’s not.

“The reality is we are a small, under-developed country doing our best to survive.”

But this small, under-developed country is pledging to remain carbon neutral for the rest of time.

In a TED talk from a couple of years ago, Tobgay says his country takes a holistic approach to life within its boundaries, having mapped out a kind of attitude to growth – leadership that has, he says, worked tirelessly to balance economic growth with social deveopment with environmental sustainability with cultural preservation. Something they collectively call Gross National Happiness.

They say GNH is more important to them than GDP – “development with values”. And it got applause from the super-rich audence at TED.

He says they manage their resources so carefully, so fundamentally, they can afford to give free education and free healthcare to all. But he talks in very cultural terms – celebrating their architecture, their festivals, their colourful heritage, including national dress. The more I watch him, the more I fancy getting a Gho for round the house.

Notice, his starting point is culture – identity. Outlook. Before getting into any environmentalism. Like a healthy relationship with their historic environment is just a natural symptom of a healthy relationship with themselves. Just, a conscious one.

72% of Bhutan is under forest, and the country’s constitution protects most of it. It means it is in good shape and richly bio-diverse – but it also makes the country a net carbon sink, with capacity to sequester more than three times the 2.2mtons of CO2 the country creates annually. That means it is helping its neighbours in cleaning up their emissions. But, Tobgay says, they export most of their hydropower, meaning they technically help to offset 6mtons of CO2 in their neighbourhood and are set to increase productivity of clean energy to almost triple this by 2020.

It was hydropower that revolutionised the economy of Bhutan thirty years ago. The challenge for the country going forward is to diversify its energy mix and its jobs market. Especially given the shrinking glaciers feeding its chief industry. A symptom of a climate crisis the Bhutans can understandably claim to have had little to do with causing.

To try to remain carbon neutral, the country is attempting to invest in new infrastructure to help everyone minimise the damage of their living – free electricity to rural farmers, green public transport and EV investment, paperless government, cleaning schemes, planting schemes. Joined up endeavours to find the next chapter of a sustainable nation. They’ve even linked their national parks with biological coridors to allow wildlife to roam as freely as possible. This is a nation that does the best impression I’ve ever seen of understanding its connected environment.

But they talk business reasonably well too, working up development investment for outside partners to help them ramp up an internally sustainable financial model. Kickstarting the future, you might say. Even as a comparatively still underdeveloped nation. Prime Minister Tobgay suggests that now is the time for larger nations to learn from their tiny Kingdom’s lessons, including its partnerships in its region.

“For we are all in this together,” he says simply. “Some of us may dress differently, but we are all in it together.”

Sounds a world away from the United Kingdom, and from United States. And from the massive challenges of mega nations in the developing world. Except, some states in modern Europe have not disimilar ambitions to a more holistic, healthy lifestyle like Bhutan’s. And Bhutan knows a thing or two about being small, uninfluential and struggling to raise development. Yet they might serve as one of the single greatest inspirations for outlook on Earth today. They prove, outlook can change anything.

In our energy supply perspectives, in all our perspectives looking forward, I’d suggest the time is now for many of us to plug into a collective volte face. It could be the most energising switch in our view of the future we have ever made.

—

GLOBAL GOAL FOR ENERGY >

Discover the UN’s take on the future of global power supply

THE REAL COST OF FOSSIL FUELS >

Flip through Good Energy’s look at the old energy system

RENEWABLES 2017 GLOBAL STATUS REPORT >

Read the REN21 data on the state of green energy globally

“Today, a fifth of the world’s electricity is produced by renewable energy… The infirm nature of the clean energy power supply will require smart grid management at scale.” >

Read the World Economic Forum’s analysis of key trends for renewable energy 2018

HOW WILL ELECTRIC VEHICLES CHANGE THE FORECOURT >

Read The Future Laboratory’s insights into the new filling station

SOUTH AUSTRALIA’S SUPPLY AND MARKET >

Watch live data from SA.GOV.AU energy output

ALMOST HALF OF ALL BUSES WILL BE ELECTRIC BY 2025 >

Read Thomas Frey’s thoughts on public transport electrification