Remember to tap in and out.

More of us than not are living in cities. This is new. It's a history first. It's a tipping point into the new human reality – a species living in an entirely self-made landscape. What will this mean for our wellbeing? And where the story of how we got here goes from here. Is the future going to look very overcrowded, with privacy a thing of the past, as both digital life and physical life noose tightly in around our living? And will this comprehensive seeming 'artificiality' seal the fate of the climate crisis, as dwindling numbers of our massed selves have any direct relationship with the land and our planet's natural processes?

LISTEN TO UNSEE THE

As well as right here, you can listen on Soundcloud, Mixcloud or in a search on your favourite podcast app.

Is the future Bladerunner‘s toxically dark Los Angelles, Judge Dredd‘s concrete police state Mega City One, Goddard’s AI-controlled Alphaville, Logan’s Run‘s plastastic euthenasio-topian DC dome city, Akira‘s neon, semi-sentient living robot organism Neo Tokyo or simply Asimov’s entirely artifically built-over planet Trantor? Or will today’s mega cities of Central and South America simply fall into sprawling total favellas with offshore utopias where all the urban designers and elite computer coders get to live, a la Netflix’s 3%?

Is my own lazy dream of the leafy European city-break lifestyle the last undivested fantasy of a privileged class? Quite possibly. Or did the great city planners of my own continent, during the lusty, arrogant but admittedly do-ish days of emperial centuries past, work out some good thinking that can yet echo forward into our resource-hungry future? And is the pattern of human living in the public realm and private life have to end up looking the same everywhere?

Cities are where all the problems of how humans live pile up into obvious challenges. Nowhere to hide them. Like the rubbish. It’s also where difference is more likely to become normal – diversity as everyday life for everyday folk. So could the urbanisation of humanty really be the cosmopolitanisation of us? Or just the ghettoisation.

Are plexiglass travelpod tubes and latex onesies the future of the city? Or single-speed bicycles, roof gardening and hemp shirts? Slum latrines and water shortages? Or cathetas, nutrient lines and VR headsets? What will the skyline of tomorrow be overshadowing?

Jeepers. Charge up your travel card. Let’s take a spin around the sustainable urban future.

VISIONS OF YESTERDAY.

Architects. What ARE they doing for seven years at university while not becoming qualified medical doctors?

It’s a question I have asked often over the years. So far not at any RIBA cocktail parties. Now, as someone who diffidently throws around the job title ‘creative’ I like to imagine I have a handle on design – especially when there isn’t one. Our kitchen looks super stylo with just recessed grooves everywhere and I care not a jot that it can be a little faffy to open the cupboards with wet hands. So, in my completely confident working ignorance of architecture, I imagine I am making a roundly sound point when I ask this opening question. Because it does seem to me that SEVEN EARTH YEARS at college learning how to do buildings, ought to have one module or two on, oh I dunno, understanding how to actually build them, how to actually live or work in them and how the jolly heck they will actually work in their contexts.

But then, I’m essentially jealous. Of creative work that shapes nothing less than brand new elements of human environment – the fabric of our experience of being alive.

Architecture, to the outsider – even the sympathetic fashion glasses and rollneck-wearing outsider – does appear to have positioned itself over the years rather closer to art – and God – than town planning. It doesn’t help that town and country planning does also appear to have positioned itself over the years a very long way from any actual planning either, massing most of its professional bodies on the burning barricades of development management. Certainly in my home country, the land-addicted UK. So who is actually planning the urban environment we all live in… and will all ever increasingly be living in?

In the age of great visioning, the early-mid twentieth century, we had no shortage of grand pompous planning ideas for the future of our non-rural living. And the biggest names of modern architecture, like the progressive jazz stars of their day, have become almost mythical in their artistic stature. And I can see why.

The lovely first lady of Momo and I made a couple pilgrimmages while on a road trip around France a few years back. Climbing a small hill just outside the Burgundy village of Ronchamp, the Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut immediately captures your vision from the rolling landscape around it. It’s confidently un-grand. Sort of friendly but striking. Flowing curves of whitewashed moulded concrete meet sharp angles of straight lines, peppered in places with almost Kandinskyesque window forms, in a Catholic chapel that feels like a sculpture from an artistic vision. A vision of some alien dwelling emerged through quiet temporal glitch into the fecund traditional bread basket of France, yet weirldy loving towards it. The effect inside is cloistered and calm, with dappled geometries of light very carefully puncturing the darkness. It’s beautiful. In a catagorical rejecting of centuries of church typology. Such creative confidence attracts, I suspect, more pilgrims of design than any other today, almost sixty-five years after it was completed. The work of twentieth century architecture titan, Le Corbusier.

You’ve got to have a fashion moniker for a name if you really want to go big, right? He was Charlie to his mates, I’m sure. But he’s arguably a shaper of 20th century urban form with no rival. 17 Unesco world heritage sites are his. Leaving a body of work as inspiring as salutory.

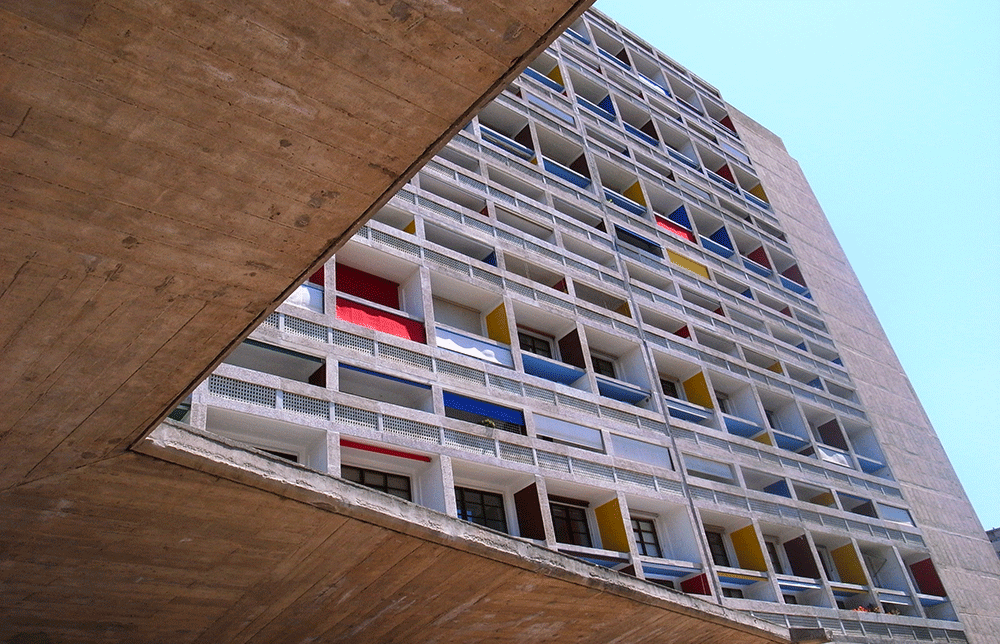

Later on the same road trip, some way south, we explored the bustling port of Marsaille. And we did what we always do – just walked. While the swiggling, turning, huddled medieval heart of the city was as casually perambulous as most old city hearts – built to human scale, in other words – we attempted to walk the hurtling dual carriageways and stumbling, sun-baked, half-forgotten pavements around the busy port to reach our particular sight-seeing goal: La Cité Radieuse.

From a distance, it looks like a modernist sideboard. A sort of long box on short legs with a couple of vases on the top. Regular window forms winking primary colours between them. The sort of thing that divides opinion. For it was, in many ways, the beginning of what we now call Brutalism.

Concrete. A lotta concrete. And a determination in density. As ArchDaily describes the whole project, first dreamed up by Le Corbusier in 1924: “Designed to contain effective means of transportation, as well as an abundance of green space and sunlight, Le Corbusier’s city of the future would not only provide residents with a better lifestyle, but would contribute to creating a better society.”

That’s not a faint-hearted ambition, is it? It sounds a world away from the demur place of worship we’d reverently stepped around two hundred miles north. But such was the work of modernists, seeing their work as almost brazenly revolutionary in their aim to “anihilate tradition” at every scale. And they were hugely influential in shaping all our dreams of tomorrow’s cities.

“Though radical, strict and nearly totalitarian in its order, symmetry and standardization, Le Corbusier’s proposed principles had an extensive influence on modern urban planning and led to the development of new high-density housing typologies.”

When we think of the great housing projects of post-war Europe and of communist Asia, it’s impossible not to see the hard lines and brutal simplicity of modernism at work everywhere. Made possible by the affordable formability of concrete, and of lots of cities to rebuild from bombing in a hurry. And Le Corbusier has come to embody the style in history’s mind. Which means he is linked as much to the great sense of failure about concrete and density and cities in the sky as he is to beautiful architecture. Too many of London’s highrise solutions to the housing crisis at the time were coming down in dusty plumes of forlorn demolition within twenty years of construction. And the same is apparently true of all the global imitators of The Radiant City.

The main project in Marsaille’s suburbs was never realised. But the key building itself still stands – and is consciously valued by proud residents. Why? When we nosed around it, to begin with up close it looks like a sort of sideways tower block in grey concrete with a great unused space for parking underneath. But the more you spend time with it, the more it grows on you in the details. Then we went inside.

It is almost a gesamptkuntswerk – a total work of art. I can’t imagine Charlie Corby approving of Wagner’s pompous oppulence but Cité Radieuse is just as confident a vision as any nineteenth century opera. The difference, apart from style, is that this is designed for living in. And it works because the whole is built by a thousand daily details of dimension, proportion, style and functionality that all feed the same idea. An oddly isolatory experiment, you might think, with a double-heighted ‘street’ of work units on the first floor and other communal ammenities. A complete human vision, is function as well as style, all components aligned. Sitting up in the exquisite restaurant on the top, even the plates and cutlery were oblong. It sounds cold in description, more ordering that orderly. But it doesn’t feel that way. The waiter told us one or two residents were still living in their high-ceilinged, huge-windowed appartments since buying them off plan in the fifties. This is a building loved for its vision and execution.

I had a similar experience on a visit to the Barbican in London.

I met a woman, while I was loitering at a shop window in the Chamberlin, Powell and Bon-designed icon of brutalism, who clearly just wanted to chat about living on the estate. And as truly brutal as the dark colour of the pitted concrete environment’s visual language around us surely was and is, here was a woman proud of where she’d lived since being one of the first to move in, in 1969. “My husband worked for the architects,” she said with coy pride. “We had to winch my grand piano all the way to the top of the Shakespeare Tower.”

In the arts center at the other end of the huge quadrangle, was an exhibition on the building of the project, right in the heart of financial London. And every sink, tap, door handle and lampshade was built to fit the aesthetic. Admittedly, that rough concrete finish wasn’t the glittering smooth result originally envisioned by CP&B but, when London council laughed in their budget’s face, they chose a deliberate-looking deliverable alternative. And the end result has integrity to this day. That magical ingredient that makes people wed themselves to something. See themselves in something.

The lovely first lady of Momo said she’d consider living on the estate just because it looked like something from Logan’s Run.

When modernist forms work well, it’s because they are in harmony with the way people actually tend to operate, artificial as such style starkly appears compared to the rustic happenstance in form and materials that is your average straw-mud barn. Tradition, mate; don’t knock it. Buildings of any type work well, I suspect, when they draw a little, accidentally or deliberately, on the ancient world principles of The Golden Mean – the idea that nature has perfect proportions for things that just oddly resonnate well with us, as products of said nature.

I have no idea if he had any such notions in mind, but the job of planning the rebuild of France after the second world war fell to Auguste Perret, a chap with whom Charlie Corby had worked at some point, but who was seen as a little more conservative. Less of a diva, you might infer. As a result, I wonder whether this subtle invisibility of the architect made for better architecture.

One of the clearest fruits of his commissioning is the port of Le Havre. It too is a Unesco site, and an oddly encapsulated bit of modernist perfection. I know! You had any idea? A whole quarter of the city built to within a millemeter of its life to exacting straight lines and design principles steeped in forget all that wiggly old crap. A style that would to this day really put off some, and really attract other saps like me. We always stay in a hotel there that’s the former finance ministry building, which gives enormous floor-to-ceiling windows and square taps and square everything in the rooms overlooking the straight, square canals. To me it’s a joy.

One pilgrimage I am yet to make is perhaps to the daddy of them all, however. Oscar Niemeyer‘s Brasilia. And it maybe encompasses the problems left behind by modernist star-chitecture, still echoing in the isolated thinking of too many pretty schemes landing on planning tables today.

It’s gorgeous on the lens, by all accounts. And the forms of the new Brazillian capital go beyond Le Corbusier’s strict straight forms and push concrete’s limits to make organic shapes in amongst the hard contrasts. It’s almost philosophical in its balance and shapes. And no one doubts the beauty of the buildings. As a BBC article quotes Norman Foster, current daddy of all architects: “There’s a wonderful optimism and beauty and light about them. They make life richer for everybody who uses them,” he says, describing some of the structures as “hauntingly beautiful” and “absolutely magical”. Bet I’d say the same. Bet I’d delight like a art college boob in the sweeping aesthetic vision of such a place.

But that doesn’t make the city a total success. For, for all those delightful, clever, human… artistic statements of living writ in building, the complete city is, by all accounts, apart from anything else, hard to walk around. Built for swooshing motorway routes – the car.

“It just doesn’t have the complexity of a normal city” says Ricky Burdett, Professor of Urban Studies at the London School of Economics, Chief Adviser on Architecture and Urbanism for the London 2012 Olympics. “It’s a sort of office campus for a government. People run away on Thursday evenings and go to Sao Paulo and Rio to have fun.”

Disconnection. Everything neatly engineered into tidy boxes and predictable flows. Lord knows I get it; I’m a bit of a pencil straightener myself. But if our grand visions haven’t delivered the goods quite yet – not least of which because developers do tend to think last about commercial access – then how the space are we going to manage a future of sprawling, haphazzard megacities? A future that’s already here, and looking anything but manicured, graceful, dazzling white in the hopeful sunshine of tomorrow.

VISIONS OF TODAY.

“The world’s population is constantly increasing. To accommodate everyone, we need to build modern, sustainable cities. For all of us to survive and prosper, we need new, intelligent urban planning that creates safe, affordable and resilient cities with green and culturally inspiring living conditions”

The Global Goal for sustainable cities and communites aims to make urban living and all human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, the UN states. What exactly does this mean?

The headline is simply ‘safe and affordable housing’ – attempting to piece together enough of it for absolutely everyone. Upgrading all our living to include at least the basics across the board – sanitation, shelter, functioning amenities and at a cost that doesn’t cripple tennants. We haven’t managed to do this in the UK yet, and it runs the fifth largest economy on Earth. A significant element of making everyone’s living healthier, however, is simply transport – being able to get around easily, affordably and safely. Especially if we’re vulnerable. Transport vitally helps a city economically breathe.

And that’s a pertinent choice of words. Because breathing is downright dangerous in many cities today. And while you might think of the surreal smogs of Bejing or maybe LA, Londoners are all too aware that before the end of its first month, 2018 had spent its EU air pollution limit for the capital. Nitrogen Dioxide levels and air particulates are reportedly breaching guidelines for health in some 44 out of 51 towns analysed in a WHO report on the UK at the end of last year. It’s currently recommended that fine sooty particles as they’re known, or PM2.5s, should not exceed 10 micrograms per cubic metre of air. Glasgow, former European City of Culture, tops the list at 16 with far too many of Britain’s major cities also in the teens, not far behind. It’s alarming that even my ‘health and beauty’-founded seaside town, Bournemouth, makes the list with a 9 – all but on the safe air limit, despite being on the coast and steeped in trees. There may be scrutiny to be applied to how these readings were taken, exactly, but it’s enough to know our obsession with getting everywhere in the entitled internal combustion engined personal car is wrecking even a quite outdoorsy resort. Pulchritudo et salubritas, mate.

The goal in this regard oddly doesn’t major on air quality exactly but sees it simply as part of the overall ‘environmental impact’ of city life, to include waste management. A simple aim that gets to the heart of the daunting problem: Where do we put everything? While it’s laudible and properly future-facing to put as much emphasis as the Goals do on developing planning systems, their scope, co-operation, function and general inclusivity, to say nothing of better disaster management planning across the board, the immediate problem is cleaning up the way we do things now.

To build spaces for humans to live in that are much higher in their density while much more efficient in their resource use, while still managing to improve quality of life living there… well that’s the challenge, isn’t it. Especially when you consider how cities tend to evolve.

Insurance giant Allianz rounds up the top twenty megacities of today with a few essential stats. And in at number 20, it’s the West Bengali capital Kolkata with 14.6 million people living in an eye-wateringly, anti-perspirant-challenging 12,200 bodies per square kilometer on the equatorial eastern border of India. Thailand’s Bangkok is just a little larger at 14.9 million souls packed into the country’s business-booming capital in a very flood-vulnerable elevation on the Chao Phraya River delta. Los Angeles, Cairo, Dhaka, Moscow and Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto nudge us up through the 16 and 17 millions, with Mumbai, Mexico City and Sao Paulo getting us up towards and over 20. New York is up there with similar numbers. The big Chinese urban hitters of Bejing and Shanghai have 21 and 24.3 million inhabitants respectively, with Pakistan’s Karachi, India’s Dehli and Korea’s Seoul all pushing the mid twenties. But it’s Jakarta that takes a big leap up with over 30 million people living in the Indonesian capital.

And the planetary top slot? Tokyo-Yokohama. Little old Japan. Nearly 38 million people live in the greater urban area swallowed up by Tokyo – the largest urban agglomeration on Earth currently. Japan doesn’t half look like the future, with all those people colliding with all that technology, in such a small bit of land. Gotta wonder if this observation is going to pay off later on in this blog, hmm.

It’s a far cry from most leafy European cities. While London and Paris top the Eurostat figures for the continent’s populations at both around the 12 million mark today, Madrid as the next biggest people centre tops out at around 8 million and all the other major cities are around the five million level. Europe may be comparatively small in continental scales, but in human living levels it’s comparatively roomy. The UK manages to be the densest population (half-) in Europe while still not living in most of itself. As the UK National Ecosystem report established a few years ago, while 80% of Britons live in cities – blimey, that’s a hipster bike goldmine – the figure for as precise an estimation we have for how much of the county is no longer green in one form or other is… 2.27%. Yes. You read that right. As Mark Easton reports:

“According to the most detailed analysis ever conducted, almost 98% of England is, in their word, natural. Elsewhere in the UK, the figure rises to more than 99%. It is clear that only a small fraction of Britain has been concreted over.”

I know you. You flatly won’t believe it, but do go check out the numbers, it’s enlightening.

Which is all very well for weary would-be gardeners, the Brits. If they want to leave their jobs and lifestyle in the metropolitan centres. Which clearly most of them don’t. And who does? It’s why we have the numbers we do.

Mark Swilling writes that the major problem in rapid urban growth has been the nature of it – not a simple densifying of the original footprints of cities, but the dreaded urban sprawl. What this tends to eat into, in a combined rush to cash in on the need for new homes, is building on the type of land that first helped attract settlements to the location in the first place – land we can grow stuff to eat in. In short, he says: “Continued urbanisation in its current form could threaten global food supplies at a time when food production is already not keeping up with population growth.”

This sort of development, he suggests, has had a particular cause in more modern decades.

“A key determinant of rampant urban sprawl – especially in North America, where it is a particularly serious problem – has been the existence of cheap oil. When oil prices reached record highs in 2008 and exacerbated the global economic crisis, the people who travelled furthest tended to be the first to default on their mortgage payments.”

In a visit to Detroit at time of writing in 2016, he says he found that of the city’s: “300,000 buildings, 70,000 currently stand empty – and mostly derelict.”

The effect was to draw people out to the suburbs and depopulate the core of the city. Not helpful ahead of the big slump in its almost tentpole industry, cars.

The model of growth that happens in the more rapidly developing parts of the world, is one that has the same effect of sprawling the footprint of cities outwards, but for much more ancient world economic reasons – the influx of poor looking for work and kind of getting stuck at the city gates. Slums. The interesting phenomenon in India appears to be that the slums evolve right in the heart of cities, juxtaposing middle class and poor with fewer illusions, but in most rapidly growing cities there are rings of more haphazard, less efficiently designed communities radiating from the urban centres and eating land.

Slums and favellas aren’t just bad sounding places for health and comfort. They are a waste of – and even block – resources their people need. And the more people flock to them, the exponentially worse that combination of problems gets.

But. Is the high minded intention to clear away slums and rehouse people always the right one? Are there, at least, things to learn from these communities that might have something to say to the whole notion of the city?

VISIONS OF NEXT DOOR.

“Finding silence in a favela is like trying to stay dry during the monsoon” says Nathan Bonnisseau in Rio On Watch. “Top volume telenovelas compete with powerful sound systems. Evangelical liturgies clash with the shouts of merchants. Residents bluntly exchange anecdotes from their respective kitchens. These communities are alive with sound and movement, but they are so much more than that.”

Culture. What is it? It is expressions of living that grow out of a community, like blossoming tendrils of bindweed, and tie it together into an identity. A mentally held idea of who you are. It’s born out of habit, ritual, rhythms of life wherever its happening that I guess usually start from a shared need – we’ve all turned up at the same place, and find ourselves needing to do the same things. Before long, we are at least identifying as people who share this experience, possibly sharing songs and jokes about how rubbish the experience is, if not actively helping each other to work it. And like bindweed, your culture can both hold the soil of your identity together and choke blooms of individuality. Identifying our id is a bit of an uneasy dialogue as we’re growing up, working out which bits give us a core of confidence and which bits are suffocating us. Trying to recognise how many cultures, in fact, are always in our personal melting pot. Such is human. But we need culture – because no settlement lives without it. The question, if you’ve been paying attention, is always: how do we encourage the more healthy versions of our cultures? The more confidently curious, sustainable, helpful. Go on, say it. Hopeful.

Well, in a hipster age of authenticity for those of us starting up coffee indies in beautifully graffitied old shipping containers in gentrified dockland districts, the idea of the cultural nobility of the slum isn’t hard to picture. It might be blown up on the back wall of your Cargo Mondo Café with the logo of your favourite blend on it. It’s always in slo-mo, through a creamy-lit lens, to the right music. And the fact that I am taking the pizzle out of the commodotisation of such poverty porn doesn’t actually remove from it the kernal of truth that we do want to recognise our humanity in the world. Even in our suffering. It’s an emotional pressure valve to all the hopeless intractability of many cultural sufferings. But the truth day to day is that in the compartmentalised modern economic world, ghettos seem a lot easier to create than cultural melting pots. Which means a lot of really cool stuff, where you live, you don’t know about.

The favelas of Brazil’s big cities are not quiet. They make so much noise, in fact, that their culture has escaped further than people who live there will feel daily that it has. When suburban boobs like me in rainy Britain can say that the soundtrack to Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund’s 2002 film City of God is among the coolest they’ve ever enjoyed, then maybe your noise is carrying. It’s being appropriated into the life score for less colourful rich people, yes, but there’s an echo of your culture on some alien person’s coffee table now. So it seems especially weird from far away to consider that the colourful noise doesn’t seem to reach its immediate middle class neighbours in Rio. Because suburbia has an awful lot to learn from such community life.

Bonnisseau asks of the favelas packed human landscapes: “What is it that makes these spaces so culturally vibrant?”

He quotes Jorge Barbosa, Director of the Observatório de Favelas and manager of a project that maps cultural groups in the favelas (Solos Culturais), who says: “the streets, the alleyways, the stairs are cultural scenes that are in fact very close to real life.”

There is energy in the mix. Human life so piled up on itself may create some chaotic-seeming problems, but it also generates vibrant collisions of ideas. Everything happens within earshot, everything happens in public, everything is part of everyone’s daily, habitual life. The apparent chaos of biological life’s evolution is how human cultural life best creates the unexpected – cross pollination and mutation. And in such an intense mix, however much there must be times extended family drives you mad, that energy of ideas gets into your blood. Your outlook. Your identity. The favelas have often been a watchword for gangland violence, but it’s never so boringly simple.

The point is, that irresistable funk of the City of God soundtrack is more than just a splendid groove. It’s not emptily cool, whether it’s the classic period funk of the story’s 70s setting, or the contemporary beats shaking the steps of Vidigal today. It is an expression of revolutionary energy. One that people in other parts of the city don’t seem to like. Music artist Anitta’s hit video Vai Malandra – go on, bad boy – illustrates the point. It’s provocatively sexed, and the beads of sweat on your dad’s brow will testify to how much it looks like more male gaze cash-in and ‘not proper culture’. It was a hit, and so polarises opinion between its empowerment and representation of black female energy, taking back the the power in the expression of body moves, and the simple objectification of women, blacks, street culture. The point though, is not this one record. It’s its cultural context – the favela.

“Funk and passinho are, first and foremost, art forms created in favelas that communicate daily life, hopes, dreams, and fears, and which draw from but constantly modernize age-old rhythms, steps, and messages” says Lucy McMahon choreographer, dancer, Human Rights lecturer. She highlights the just splendidly named Casa Do Funk school of creativity, which teaches young people the moves and the music of the favela as steps, beats and words of empowerment and identity. As she explains, the Rede Funk community: “celebrates and teaches ‘conscious funk,’ a style that tells of the violence, pain, joy, community, and rebellion of artists’ everyday lives.”

But the recognition of culture tends to be the problem across connectivity gaps. While perhaps rather ‘whiter’ parts of cultural town set up actual groups like Funk Is Trash – with posts saying things like: “criminalise the funk, a favour to society!” linking it to violence against women – is too right on to imagine how many in the favelas might echo McMahon: “Funk offers a chance of social mobility that is entirely self-created, emergent, and independent of any top-down social project, whether the mobility of the music from the favelas to other countries and into middle class homes and universities, or the mobility of dancers and MCs to positions of success and influence. It has the potential to threaten the racial and class hierarchies on which the Brazilian status quo is built on” she says.

Culture empowers and culture divides. And its always there, bringing empty buildings to life in one way or another and making them communities.

Interestingly, the connectivity gap may often still be old fashioned physical – transport. Getting from home into the Asfalto is, Barboso says, too easily prohibitive: “The priority is not equipment, it is the territory,” he said. “Having a place to realize oneself, to live together and exchange, this is what potentializes an entire community.”

The favelas illustrate the richness of human life in their own cultures, and the serious challenges of spreading the different types of wealth and opportunity across a whole city. But there are some physical principles at work in our psychologies.

Next time on Unsee The Future, we’ll be concluding our outline look at the challenges facing urban life in the 21st century, as more and more people flock to the city. Such a massive subject, I’ve opted to slit it across two episodes. And Episode 8 is still a meaty one – and still manages to barely even begin to interrogate all the key things in play in our built environment challenges looking forward. But in it, we make a start to grasp some principles that may come in handy when tackling human community development designs. All as just one part of our connected outline of the potential plan for the more hopeful human-planet plan.

DISCOVER THE UN GLOBAL GOAL FOR CITIES >