Don't leave the house.

“Unsee The Future, the unreal experience. Download the adrenalin, embody the excitement, thrill at the life-likeness, feel the heat from all the explosions, weep with all the orchestral sentimentality, gag in real time with the smoke machine, sense the scary bit coming and try not to trigger a seizure with all the flashy lights, ruin the atmos and sense of narrative urgency by mucking about with the live actors trying to put them off their lines – be transported to another dimension! Another reality. All through our patent Your Ears Connected To Your Brain With A Bit Of Heavily Programmed Entertainment™ interactive technology. Book your free tickets now by doing nothing and basically continuing to just listen. Without leaving the house.”

Don’t leave the house.

..Or, for a real thrill, you could just go back to the news.

ALONG WITH RIGHT HERE, YOU CAN LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD OR YOUR FAVOURITE PODCAST APP.

Header photo by Tess on Unsplash.

>pooof<

Well.

Then.

The 2020s, eh?

Immediately a bit of an experience.

A suddenly really low budget home made one.

As I speak, the usual Earthworld ride is shut, for some pretty serious maintenance. And suddenly all the different components of the human planet – all the different experiences of it – are thrown into a dramatic new light. One that no theme park ride or 4D screening could come close to squirting in your eye. In a blink. Everything of us. Every one of us. Globally. Our usual experience of coming and going and rushing about or mucking about and hoping for this and working for that and praying we’ll manage to avoid a public panic attack for one more day and presuming the system will keep creaking along and deliver us something or other we were expecting, even if it’s disappointment and injustice… it’s all been just… stopped.

Sort of.

Quite the reverse for you, if you’re now considered a key worker.

As head-spinningly swift as this new world’s arrival has been at the beginning of 2020, it can take a while for change to truly dawn on us. It took a significant while to look like anything had stopped in most of Britain’s parks, for example. Or on the beach where I live. Because the other thing that had stopped in my home country – when I think all of us here imagined IT NEVER WOULD EVER AGAIN – was the rain. After three years of the grinding political social separations of Brexit and the dawning realisation of global species collapse under the weight of our lifestyles… gorgeous spring weather just turned up. The sunlit uplands appeared! ..At just the weekend we in the UK were supposed to be closing our doors and Googling Italian isolation techniques. Dreaming of the halcyon days of scoffing at know it all climate kids who should be in school, thrumbling along to the Co-Op in our Rangeys and deporting anyone with a slight accent.

So, in this sudden ALL NEW wartime spirit, as if we needed another, we naturally pulled together quickly as a nation, by pulling our kids out of school, hoping all the foreign nurses we told to f*** off would please come back, and swanning about seafronts and picnic spaces and woods and high streets, blithely beating each other with the last bog roll for fifty miles. Like we were all determined the end of days in ol’ Blighty would be a lot more It’s A Knockout than Survivors.

The first warning chill for many might have been Eurovision being off for the first time in its 64 year history. And not because of Brexit.

This all was, of course, just the first cuckoos of spring.

Coronavirus Disease 2019, or simply COVID19, caused by the newly identified virus SARS-CoV-2, has changed everything, and brought system change ideas into abrupt sharp relief. And I’m not sure if it’s now Pandemic, or War Of The Worlds or Independence Day or rather obviously the incomparably bleak 1970s British series Survivors, but the story we all thought we were in has changed overnight.

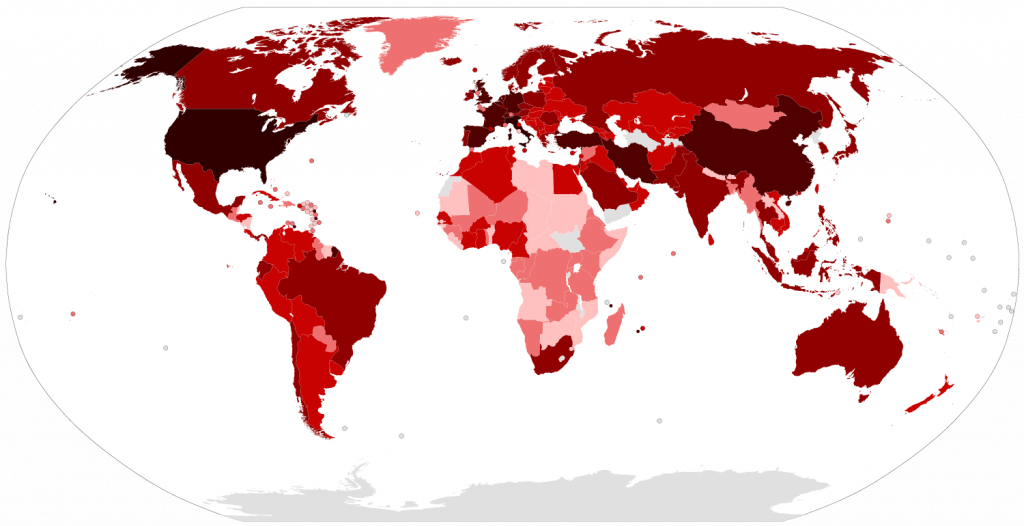

In a deeply individualistic, dominating global culture, how the hell are us stoopid entitled lot, waddling about with “our own ideas”, going to cope with an enforced fundamentally disruptive shared experience? And on this scale? As blossoms bloom in the northern hemisphere, at least a quarter of the world is in official lockdown and barely a handful of territories on Earth are left not reporting infections. Nothing in history has brought together the elements in play for us as a collective generation at the start of the new twenties.

Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 by country and territory (as of 31 March 2020): 100,000+ confirmed cases 10,000-99,999 confirmed cases 1,000–9,999 confirmed cases 100–999 confirmed cases 10–99 confirmed cases 1–9 confirmed cases No confirmed cases or no data. By Pharexia and authors of File:BlankMap-World.svg – This vector image includes elements that have been taken or adapted from this file: BlankMap-World.svg.Data derived from Johns Hopkins University CSSE, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, New York Times, CNBC, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=86236603

As we continue to dial through some of the fundamental elements of the human planet and its crises with Unsee The Future, we’ve been going beyond the foundational components, helpfully defined by the UN’s Sustainability Goals, and exploring some themes around and beyond them that are shaping our times in our minds at the moment – democracy, travel, the notion of disruption itself. And I’d come next to the word experience, because it’s been a word so thrown around marketing and tech over the last decade. We all want better experiences, apparently. Poor us.

Our obsession with tech tends to throw up frequent press reference to emerging platforms like VR and AR and XR – Extended Rebellion or Extinction Reality? – in sort of sideshow gimmicky ways. But in my research into this episode over an extended period, it’s clear this theme runs back to some pretty primal human sense making.

And where are we living now, if not in a whole new normal, demanding some rapid primal human sense making?

So I think I’ll start by suspending us from our bunkered new reality for a while, and take us back to the distant past when we boarded planes without thinking about it in search of something to shake up our daily humdrum.

Because in our search for better experiences, the stressful but somnambulant rhythms of the robot world eventually can get us yearning to do something the insuranced system doesn’t like to encourage in its fleshy workers. Taking some bloody foolhardy risks.

TRIPPY EXPERIENCE.

“There comes a point, fairly quickly, when you need to decide whether to freak out about it or embrace the challenge” said my dear friend Sebastian. “Embrace the expectation that every moment, for yet another day, could be your last.”

Driving across India in a tuk-tuk is a fairly certain way to feel a lot more alive. Precisely because it sort of risks your very life on a planet already full of terrible threats in a resoundingly pointless way.

Buddying up by drawing straws each morning may seem a fair way to decide who drives, but among the many life lessons that will come at you quickly and unexpectedly on an adventure trip with your mates is the simple one that there is courage involved in surrendering the throttle to some of them. And you know exactly who they are. As a military copper I once knew said to me after his first pursuit driving lesson on the backroads of Dorset: “A damn-sight scarier than taking the wheel at one hundred and ten yourself for the first time is sitting in the back when some other bugger does.”

Lots of things will come at you on the roads of India. Anywhere in India. Absolutely everywhere in India. Unrelenting, utterly chaotic seeming, pupils-dilating traffic stimulation – elderly buses and trucks and Premier Padmini taxis, loaded to the skies with vegetables, and plenty of sturdy old hooting Ambassadors and thrimming bicycles and nonchalant pedestrians and ambling cows and, oh you know. We all know. I’ve not even been there and I know. I can smell the earthen heat and adrenalin from here. And I also know the only way to survive such an experience with your nerves intact is to plunge in headlong and swim. A lesson I originally wanted to learn driving around the Colosseum in Rome for the first time, back when you still could. I did feel a bit more more alive doing it, even as my insurance documents smelt of sulphur for a few minutes.

On their very first morning navigating the heat of Kerala, on a trip organised by another dear mate, Julian – who himself is responsible for so many of my own greatest adventure experiences over the years – “plunging in” for one of Sebastian’s cohorts, meant almost immediately ploughing in to some poor local chap’s brand new Tata. Illustrating the interesting notion that the chaos of an average morning on the highways of the sub continent have an odd kind of accepted cultural logic to them. The young chap on the receiving end of an unwanted auto-rikshaw, driven in blind panic by a stupid tourist, jumped out of his pranged saloon in distressed tears. Like a collision was an unthinkable surprise.

As trucks and cars and bikes and taxies swarmed around the static scene in the middle of the highway, meeping and thrumming to get past, the chap spoke no common language to Sebastian and Julian’s little band and so a sister was called. Who arrived momentarily in the gathering morning heat and smog to translate effortlessly into English. A negotiation was enacted around a simple cash recompense. Nerves were steadied. Tuk-tuks were unentangled from new Tatas, friends were on their way again and gossip was spread briefly around the city about more saps from Europe who couldn’t drive.

Despite not being buddied up to ride with that particular cohort that morning, Sebastian still wondered if he was managing to draw the short straw most mornings. For he kept ending up with another friend in the party who had become legend after Julian’s stag weekend in Norway a decade earlier – local neighbour to Julian’s Norwegian best man, Jungmagner. Jungmagner became legend partly for his ability to drive a John Deer tractor expertly while being both very saturated with beer and very not in the cab of the tractor at all for much of the time, but also simply for his unrelenting cray. Probably more even handedly described as energy. He naturally applied his energy to driving a tuk-tuk across India with verve in every moment and it can be said that Sebastian went on a fairly deep inner journey during his time on the roads of Xxxxx province.

“He was of course,” smiled Sebastian to me, in the leafy garden of the Troubadoor in Kensington, “by far the best driver of us all.” Jungmagner never crashed.

Experience. To find it, you do have to be prepared to leave home. And seatbelts.

We’re apparently wanting a lot more of it. A much better it. A better retail it, a better learning it, a better user it, a better smear test or prostate examination it, probably. What we seemed a little less bothered about in recent years is it on prospective CVs – as employers we seemed to find ourselves saying in the 21st century that a desire to create better client experiences because of all our rad travel experiences looks rather more attractive on a resume than: “Yeah, I’ve done quite a lot in your sector and know what I’m doing. Plus I won’t nick the stationery.” Doesn’t sound very influencery.

Even in the relentlessly ageing recruitment market… we’ve been wanting a more interesting career experience, now that we know we’re going to live into the 22nd century and have to work all the way to the grave.

And this attitude undoubtedly reflects better on us for actually finding jobs in all those extra decades; adaptability. Creative aptitude. Curiosity. Empathy. They’re all such experiency words to signal how futury you are. And how not a mindless algorithm but in fact how easily bored with the rubbish experiences of decades behind beige CRTs and filing cabinets in planning departments.

We want better. Dammit. We may have only so much time and so much money but we’ll increasingly part with more money, so it seems, to have a better time of it. Whatever it is.

As a Futuremade report headlines it: “In the future, consumers will want to use all their senses to be there, even though they are not physically there – to deeply experience entertainment from the comfort of home.” ( https://www.skygroup.sky/corporate/media-centre/articles/futuremade-the-new-dimensions-of-media )

What is it about this word experience that for the last few years seems to have been sticking so easily to so many actions and ideas we used to do quite ordinarily without thinking about it? If it’s just advertising wonkery ramping up our expectations to demand a coffee experience, and not just a cup of Mellow Birds from Alan’s caf, you dreary sap, then I hate to break it to you but we might well be already in the inevitable process of – spoilers – discovering how all these *new* experiences are as disappointing as all the old ones. And how infuriating without adblockers.

Well, we’re going to do a deep dive on that now, aren’t we? We’re NOT physically there. At work! And all our senses are very tuned indeed to whether we’ll ever get to work again. Or get to wipe our arse with something soft.

What have all these almost petulant demands for something better in the everyday really been about, when the everyday of the early twenty-first century, before the low bandwidth Covideo era, already gave millions more of us than ever before more food, entertainment, colour, music, storytelling and recreation than we could ever have gotten through? Back when we were busy, anyway.

How does that increasing supposed demand for more meaningful experiences fit with those technology trends pointing towards more mind bending experiences? If, as August Bradley puts it: “There will be opportunities in virtual reality that just shatter our preconceived notions of what reality is, that make us radically rethink reality” how might we prepare for this supposedly inevitable business development? Or is the reality of business already now shattered? ( https://www.spreaker.com/user/disruptorsfm/disruptors-fm-159?utm_medium=widget&utm_source=user%3A11432377&utm_term=episode_title )

Around this Consumer Electronics Show stuff, with more of us living longer, did anyone think it wouldn’t be a bad idea to start trying to channel all those possibilities into some more robust economic outputs? Preferably some both less fetishising of youth and its insecurities and less utterly reliant on youth’s cheap workforce? Could we plan to do more than imagine how to enhance medical or surgical experiences, and push back into the values that drive our experiential human demands in the first place. Like maybe trying to address why ever more of us are addicted to reality-altering chemical experiences already, for example.

And if more of us are still likely to be simply working in virtual environments in the future, for a much more flexible interface with design, problem solving, and making the most of bot processing as fleshy minds, will our wwellbeing be increasingly linked to minimising the experience of the real world, boiling away as it might be around the crowded refugee camps of the climate crisis, or the infectious middle class cess pits of Waitrose?

Given that everyone seemed to think that massive online multiplayer Fortnite was Very Cool Indeed for calling time on its gameplay in 2019 by blowing up its entire world environment into a singularity, is there a nihilistic hint among players that we’d all secretly like to blow up the world, fall into a black hole and start again? ( https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-50038597 )

If so. Have we just been granted our wish? Or the first chapter of it?

Undoubtedly, remembering the disappointing high street of ordinariness, all that advertising wonkery, trying to ramp up our expectations about how good a coffee experience was supposed to be, reflected something deeper – that we have all been desperate for something to get the blood pumping again.

And that could just mean getting out in the rain. Or it could mean the opposite.

USER EXPERIENCE.

Do you remember Second Life? ( https://secondlife.com/ ) Sort of Lawnmower Man made actually virtual. As you know, cyber geek that you are, it is remarkably still a thing after its launch in the summer of 2003. And it apparently still has not so far short of a million active residents. It’s essentially a sort of massive online multiplayer like Fortnite but with two key differences to a typical game – it’s significantly user-generated, and its gameplay is about experience over achievement. “There is no manufactured conflict, no set objective” as developers Linden Lab insist.

You’re basically meant to wander around exploring and making things and spending your in-world Linden Dollar on whatever makes your second life feel nice. Not many of my colleagues at Play Magazine twenty-plus years ago understood why I chose Pilot Wings as my companion game to go with my bonus payment N64 console, but man was it restful. Just puttering about that 64-bit world in a gyrocopter. ..I was never cut out for gaming.

Founded by Philip Rosedale, Linden Lab was always intended to be an immersive experience business and the early idea for Second Life was amusingly committed to hardwaring its way to delivering that. In fact, the plan seemed to be to build a haptic gear company and Second Life was just the software testbed for it. The virtual playground itself, however, was the bit of the business that took off and to this day The Rig is apparently still in boxes in a Linden back room. ( https://secondlife.fandom.com/wiki/The_Rig ) But some, like Wagner James, wonder if Rosedale’s 25 year old vision of strapping into body sensors surrounded by big boxy monitors while essentially sitting in a medieval full body brace isn’t nearer the mark for immersive tech than a lumpy Oculus strapped to your face.

“The Rig was a totally different approach to VR than the HMD-centric devices on the market now, which continue to suffer from slow sales” he suggests. “The Rig, by contrast, centered the VR experience not on sight and hearing, but the user’s motor system, and proprioception – ie: the way we unconsciously perceive ourselves and the world around us through physical movement.” ( https://nwn.blogs.com/nwn/2017/10/philip-rosedale-vr-rig-linden-lab-high-fidelity-second-life.html )

It’s a weird longing for total, immersive escape, isn’t it? Something that also beautifully illustrates the quaint vanities of tech’s stunting limitations compared to our imaginations – the original Second Life promise became an era-locked style. To this day, Second Life looks like a sort of K-Pop tribute act to a Neuromancic view of the future, even as its values were meant to be more Burners-Lee utopian. Rather more in line with William Gibson’s neon corporate near future, Second Life was one of the first platforms for Virtual Reality Retail, where In Real Life brands felt they had potential new real estate to swoop into and sell from.

But it hasn’t killed the idea of escape. Escape in there. To hide in The Grid and start again. Look great in a Tron jumpsuit, fly, be better able to express yourself. And crucially, to build your own world – not just an avatar but spaces around you – a life around you. It’s a principle that Minecraft simplified in style right down to something that felt as much a tribute to Lego and physical building blocks as it did 8-bit video games in 3D. And a human appeal that Facebook used to hijack the liberal democratic world.

So how do you design an escape? Or any experience? Before you can play, you have to build the toys, understanding they’re really tools.

For all the bitter romantech appeal of cyberpunk, three decades into its neoliberal reality, we’re getting very used to trying to analyse real human experiences in much more systematic, techy ways. Demystifying what makes the human animal react to stimuli. The practical codification of UX.

UX, or User Experience, is something I first sneered at a little – just a little – as a designer, because just like the term Design Thinking, it initially seemed to me merely a slightly tossier way of talking about the creative process and purpose of, um, design. But as I’ve found since working with UX specialists, it’s a useful methodology to analyse human interfaces and interactions, to work up better flows. It’s all just different ways of understanding, isn’t it?

As the Interaction Design Foundation puts it: “UX is critical to the success or failure of a product… but it’s grown to accommodate rather more than usability”. ( https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/the-7-factors-that-influence-user-experience )

The quality of a user experience, for example, often of online products but of anything in our built environment at all, is first determined emotionally by how valuable, desirable and credible it seems to us, not just how also useful, accessible, findable and actually useable. Seven key factors you could say a user journey with a product has to flow around smoothly if people are to wed to its brand and invest in it. Which all sounds soul-destroying put like this, but does reflect what we’re actually doing.

What’s driving this re-appreciating of design? We are clearly wanting much better experiences of the stuff we are dependent on interfacing with in the modern world, perhaps because most of those tech experiences are often still frustrating and still boring – much like the term UX. A good mobile app might be a few degrees more human than using a glorified typewriter to shop for a new jumper, but not many.

But there’s a lot more to the recent cache of the word experience than a uniform customer journey. For one thing, it’s interesting that UX can quickly get a bit philosophical. As UX Magazine puts it, you’re never designing a uniform experience anyway, as: “The user will always have the opportunity to experience it in a unique way – in part, because cognition is unique to each user.” ( https://uxmag.com/articles/cognition-the-intrinsic-user-experience ) We’re talking Cognitive Barriers and Cognitive Load here, people, and that’s before we even begin to consider the narrative biases a user is bringing to an experience ahead of whatever it is you’re hoping to get them to do. Or feel. Or buy. Or leave on the bloody shelf for someone else, you selfish arse.

There’s so much energy around this still very engineered analysis of human behaviour that you’d better believe the Experience Economy is a capitalised thing – first coined somewhere in the 90s and famously outlined in Joe Pine’s book. It’s the idea that especially since post war manufacturing, businesses are expected to orchestrate memorable events for their customers, and that memory itself becomes the product. Leaving users removed from direct contact with actual commodities.

Talking about his mother, like so many mothers and not fathers apparently, making birthday cakes herself when he was young, using just cents-worth of raw ingredients, Pine says brands then came along and put together those ingredients into a packaged experience – a more expensive one, and a more regularised one. Which unlocked an obvious trend.

“Now,” he said, twenty years ago, “not only do we not bake the cake any more, we don’t throw the party any more. We outsource it. To some other company that is going to stage the experience for our kids.”

Whatever the business or theatre, about cakes or cars, right in the middle of ordinary robot life today, the experience economy blatantly taps into some very un-techy, non-engineery human expectations.

Myth, mystery, storytelling and senses.

Despite the billions banking on technology, it’s not more engineering we’re really longing for. What we want a lot more of in our first life is, of course amigos, art.

Don’t roll your eyes. You’re no fun when you’re like this.

RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE.

Artist Tony Spencer ( http://tony-spencer.com/the-cube/ ) is interested in how sound and material can explore a sense of sacredness. Based in Southampton, he spent a residency in Gambia, partly exploring traditional ritual and rhythm and dance, but his sculpture The Cube, shown as part of Bournemouth Emerging Arts Fringe back in April last year, looks at first glance like a very nice bit of furniture.

It’s essentially an attractive wooden box on wheels with glass marbles set into it showing through a densely black interior, when its doors are open, all just big enough to accommodate a human, scrunched up. But far from some sort of magic trick, it’s an exploration of sacred geometry, with sound and light.

“The Cube represents the base chakra and earth, which is why it was birthed during a full moon on an ancient burial site at Old Winchester Hill” he told Maija at CAS. “It was quite a journey pushing it up the hill at two in the morning. I climbed inside into the dark interior, closed the door and drilled the holes for the marbles with a brace drill and bit. It was a ritual which let in the moonlight.” ( http://www.chapelartsstudios.co.uk/blog/featured-artist-interview/cas-artist-tony-spencer-talks-about-mystical-art-and-immersive-sensory-experiences/?fbclid=IwAR36qXMpLKUPbJfQm5rQHRx0_ZqON_cV-ZTZClFc8MeCGjPL-cB90Uet1J0 )

He then exhibited this in the Sovereign Centre in Boscombe. And it got quite a reaction.

“I Introduced people to what I’m trying to convey through the sculpture, it’s ancient mystical geometry which relates to sound as healing” he said. “I pre-recorded the sound on the Saturday morning before the festival started. I used three Himalayan singing bowls and the principles of sound healing. Within a ritual I cleansed my energy by burning white sage, and set an intention that wellbeing would come to people who experience the work. I said a prayer to the four elements, and used sweet grass to call in support from ancestors and spirit guides. There was an energy and intention to this ritual which I put into the sound I created; this is part of the enquiry, to see if it creates an effect of wellbeing.” Perhaps even in a drab retail space. And he adds: “The public engagement with the work was quite profound.”

People of all ages, interrupted in their mall shop by this demure sculpture, seemed to open up to the experience. In one interesting instance, as Tony says: “There was one boy who was really hyperactive and dismissive, who said: “What’s this supposed to be, the sound is annoying”. He climbed in and came out transformed after he spent some time relaxing into the space and the experience.”

This may not be a Merlin Entertainment-scale experience, or even The War Of The Worlds Red Weed Bar, but far away from the pistons and screams of Alton Towers or the vast geodesic arena of the docklands O2 or the renaissance round of the Globe theatre or any proscenium arch or white cube gallery or even a single screen, in the retail reality of a local high street, humans found something moving about climbing into a musical box. With a little ritual intent attached to it.

What are we tuning into there?

Are we feeling increasingly starved of experiences that aren’t purely transactional? There in the shopping centre.

Simon Reynolds, writing in Pitchfork, asks: “Why has so much electronic music this decade felt like it belonged in a museum instead of a club?”

It’s a question that sounds like the reverse of leaving the academic head for the tribal body. After all, the dance floor has a history of rebellion as well as ritual. As Jeremy Deller’s beautiful documentary, A secret history of Britain shows, to bewildered school pupils of today appearing it, the creative succession of seemingly high minded modernist sound experiments in Europe to the gay clubs of New York, in disco, through the new wave into the house sound of Chicago and the rave scene in the UK… all these elements in this sequence of musical evolution were art forms as instinctively about finding identities in the gaps of the modern world machine as they were about finding some joy. But even the club can be commoditised, and perhaps new musical movements are emerging that need to declare some overt new intellect. Some vision. But interestingly, this new experimentalism doesn’t have to stay all academic.

Simon Reynolds’ lengthy piece explores the rise of something perhaps a bit more intentional than habitual dance music production. Conceptronica – which clearly had me at the very title. While I’ve always said that every LP should be some kind of ‘concept’ or considered a rounded experience, my own musical work with Momo:tempo has rather more music hall in its electronic tone than arch tone poem. But whether it’s deploying witty one-liners or boofing great beats or evolving melancholic soundscapes, for me electronic music’s great appeal across it’s huge variety has always been it’s sense of world-building and adventure in storytelling. And in Conceptronica, some prog rock poetic confidence has fused with Amon Tobin-esque sonic bricolage (write that down) and a lot of overtly beyond-sonic elements – because it’s very much designed for a live environment. A much bigger musical experience than just sound.

It is, he suggests: “A quest for another sort of authenticity—the paid-for privilege of being present at an Event” not just a gig, and it: “Fuels what Amnesia Scanner call “the experience economy” of today’s festivals. Just as much as bottle-service raves on cruise ships or EDM gatherings like Electric Daisy Carnival, experimental music festivals are selling exclusivity and a sense of occasion.” ( https://pitchfork.com/features/article/2010s-rise-of-conceptronica-electronic-music/ )

In all my readings and conversations with experience designers lately, the go-to references are Punchdrunk Theatre and Secret Cinema. And this sense of theatre and occasion and hidden knowledge combined, along with just a little fourth wall breaking, are encouraging people to part with some healthy ticket prices to take part.

A friend of mine from a developing gang of experience wizards, Raj Samuel, has with his project Malice Arts successfully produced a whole series of playful pop up events that may sound to you like the coolest urban parties you imagined you’d be getting exclusive tickets to a lot in The Future. But their depth of concept and detail takes work that seems to pay off. He described to me in loving detail The Lion The Glitch and The Wardrobe, which invited its select guests to: “Step into a parallel universe of bizarre stories, curious characters and immersive experience set to a backdrop of eclectic music.” And in his latest event, The Blizzard of Od, the team of creatives that Ramy pulled together seemed to out-do themselves. But, whatever the cost and subsequent ticket prices required to make such one-off world building happen, it’s clearly driven by love – it takes it to make it, and to want to be there so whole-heartedly. And people seem hungry for it. (http://enter-malice.com/)

It translates even onto many local high streets. While a century of pleasant department store retail experience came to an ignominious end with the final closure of Beales in Bournemouth this winter, escape rooms have been popping up all over town.

These experiences don’t seem only about escape and amusement, do they. Lord knows, much as we’d need it now, these playings seem a touch more meaningful in their implications than empty immersive imaginative diversion. Perhaps especially in a time when many of us are also suffering from a touch of franchise fatigue; as I’ve written about elsewhere, it does feel that the much loved comfort blankets of some revisited stories currently feel more like empty theme park rides than engrossing character pieces or moral fable. It’s a bit hard to care. Much feels like Ready Player One to me – nostalgia and production turned up so high, it’s almost as if millennial makers carrying corporate budget burdens actually want to keep real emotional engagement at arm’s length. Lest we truly face the depth of how we’re feeling.

Or they’re just not sure what to really be saying. This seems historically disappointing, when you pop your head up and look around at the world. Such projects, stories, could be used to explore… rather more right now, no? Do we not, in fact, really need them to?

In the musical worlds, Conceptronica at least seems to want to attempt to explore something, ranging from near-future implications to outright politics across its artists; Jack Latham’s project Jam City ends its bleak surveillance culture video to Unhappy with the words: ““Stop Being Afraid—Another World Is Possible”.

Feels like a relief to me to have artists wanting to challenge the status quo anywhere these days. But – is it me? Any tidal wave of cultural derision or vision seems still only a few gentle laps at the toes down at the beach club night. An artistic inertia seems to grip the planet, when it comes to looking forward. That may partly be down to the shared stupefaction of crisis shock that we’re all feeling, so overwhelming and impossible seeming have been our planet crises already building up around us. But if there is a discernible stuckness of daring among any professional artists, it’s also a question of economics, as Michael Pinsky put it at an Inside Out Dorset introduction to his Pollution Pods experience, showing on Brownsea Island in the autumn: “So many artists know they are making work for extremely wealthy markets – patrons who don’t want artists going too far in upsetting the status quo” he told me.

Of course, now the status quo has been upset for us. And just what is going to come of this creatively?

Before the strike of Covid 19 there had already been that growing impetus to find better experiences and it was outside the rarified conceptual spheres of The Art World or the sickly theme park rides of corporate franchises. One that came from something a lot more fundamental than even wanting to be cocooned from change or disaster, and it may truly flower in the pandemic years.

I think a thing has been gnawing at us that goes beyond even a desire to feel more in control of our environments and narratives in times of chaos. After all, while future programmable realities will help us do more to address that Me-centric, choice-obsessed culture that retail and brands have seemed utterly hypnotised by, a huge part of the desire for more immersive experiences involves a good degree of trusting surrender. A more meaningful ghost train.

It’s a desire not seeming disconnected from the rise this century of attendance at yoga lessons, to me – surrendering responsibility for even personal movement, being told how to move our bodies through physical shapes, right down to the breathing. Surrender.

Among other things, I think we also really are quietly longing for a lost degree of shared ritual. Are we about to write many new ones? Firstly across shared screens, locked away from physical contact. But will this be the quarantine that fosters our desire to truly break out of some old ways of seeing?

Because traditional rituals are experiences at odds with the way we’ve come to expect storytelling in recent generations. One we don’t even see any more, but which was once a maverick new language that pioneers learnt in the saddle, but which now feels like true prescription. The rectangular frame.

What the actual ruddy hell is the rectangular frame all about?

That prescriptive single vantage point is, when you think about it, very demanding. Lord knows, I love the experience that’s on rails – the cinemascope crop, the recorded musical arrangement, the big theatre number, the Jurassic Park lab tour. But it does a lot to tell you what to do and think, that edit. It’s a thing we’re very used to surrendering to. But are we wondering if it’s even possible to break out of it a bit. Because, 16:9 or story format, it is almost all we see the world through, that frame. Even before we self isolated with broadband.

As James Fox says with some wonder in his series The Age Of The Image, what we take for granted now as film language was cleverly worked out to help audiences follow a story in a brand new visual age, nearly a century and a half ago. What was known then as The Continuity System – establishing shots and the fourth wall and all kinds of conventions to lead an audience around on-screen events without getting confused. The theatrical illusion of movement from projecting a rapid sequence of still images may have elicited some heightened emotions from its very first audiences, but pioneering filmmakers quickly felt you could take people on a much deeper journey than falling off their chairs in terror as a steam locomotive looms at them – if you could enable them to follow you.

“ These pioneering filmmakers were constructing from scratch an entirely new visual language; a visual style as fundamental as Renaissance perspective. A style so slick and so flawless that we don’t even notice it. And like perspective, the continuity system proved phenomenally successful. For the last hundred years pretty much ever film ever made and indeed every sequence in this programme obeys its rules.”

We really do want to throw ourselves into imaginative escapes. We seem wired to do it. And to then imagine for a long time, there is no other way of seeing things.

“From prehistoric cave art to Gothic cathedrals, grand opera and classical cinema, humans are clearly drawn to immersive experiences in which our whole bodies are enveloped in creative content” says Jon Dovey, Project Director of the South West Creative Technology Network, a showcase of which I attended back last spring. But he suggests the most instinctive human example of this desire is very physical.

“The most enduring, popular and productive form of immersive cultural experience has been the dance floor” he suggests.

Music and sound are, of course, ineffable experiences of the imagination. The comparative rigidity of the written word and then of the screen is hard to compare with the unbounded experience of closing your eyes and opening your ears, and then just beginning to move. It says something that we’ve needed anything as convoluted as Conceptronica to help us rediscover what music is about. Transportation to elsewhere.

“Let’s be honest,” says Mike Phillips, Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts at Plymouth Uni, “if we wanted to make the kinds of immersive experiences we dream of, we wouldn’t have built these clunky technologies.”

He posits in passing the idea that perhaps Leon Alberti’s book Della pittura, is a turning point to blame for the strict conformities a lot of storytelling experiences have baked into them. ( https://www.scribd.com/document/78928307/Alberti-Della-Pittura ) It’s a fifteenth century publication from an early Renaissance master, distributed in the eminently shareable medium of print and pointing towards a huge culture of Mastery and properness and hierarchy that fell out of the Renaissance as much as new ways of seeing God and painting alike. There are Right and Wrong ways to do art, some decided. I’d say it prefigures something systematic in the Enlightenment, history fans, framing perspectives and practices as acceptable or unacceptable. Lord knows one of the best ways to enjoy music is bickering about what’s good and bad, but in a bid for greater interactivity, storytelling doesn’t get much less prescribed strapping on a clunky VR headset and blocking out all natural peripheral vision than sitting still in the darkness of a picturehouse.

But what immersion does, even in the currently limited technical delivery of VR designs and kit, is to rather fundamentally muck about with the way we’re used to telling stories. Because it suggests that, forget the movie frame, “there is no vantage point” in the story, as audio artist Duncan Speakman puts it.

“Immersion might mean looking outwards, listening outwards,” he says. And it’s: “Something that already exists, something we live with all the time – immersion is a way of describing the way we exist deep inside complex tangled ecologies.”

Which sounds like an emerging creative language of our complexly troubled times if ever there was one. But ordinary farty twerpy you and I navigate this stuff every day. Life is immersive.

Will it be designed immersive experiences that begin to really speak into our fears and connect us with the possibilities on the other side of them? Partly because, as Julia Scott-Stevenson puts it: “We are not a constant dot.”??In a time of potential awakenings from liberal individualism, this sounds way-Buddhist to me, man.

“Climate armageddon, the rise of the far right, the arrival of our machine overlords?—?it’s easy to imagine that the future is an unsalvageable hot mess” she says in her Manifesto for Immersive Experiences, Virtual Futures. “But what if I told you that an immersive experience such as VR might help us find a way out?” ( https://swctn.org.uk/2019/03/12/virtual-futures-a-manifesto-for-immersive-experiences/ )

It’s a way to take us into spaces we couldn’t otherwise experience, for one thing. And, when good, such experiences are about very emotionally activating moments – of encounter, bewilderment, physical agency and doing, and an embodiment of something as yet unseen. Of possible futures.

This sort of stuff speaks quickly of connection and care. Of unlocking perspectives. New ways of seeing.

This might not be what big brands have in mind when they talk of better experiences. It’s easy to see why tech companies slightly miss the yogic truth and love the hardware bits of this type of experience. Not simply because that’s units they can count and so make easier sense of selling, but because it does all sound like a disconnection from ordinary boring life, which customers seem desperate for. But the people working within big brands are tapping into the same spirit of the age, arguably, and some interesting things can spill out of such experiments.

A problem here, is that most of our mainstream expectations about such stuff are increasingly being built around one particular new societal bit of infrastructure that’s been threatening to land for years. One that’s talked about much and is becoming as hallowed in some quarters as vilified in others. And it’s hardly likely to diminish now the entire planet is relying on working from home.

I speak of course of the great tech hope turning point delivery system of 5G.

Will we realise our new rituals, will all our grinding gears of experience expectations finally be freed to spin smoothly when the fifth generation of the mobile network finally gets beamed into every living cubic inch of our public and private life?

—-

And there we pause our experience of experience. Take a breather from the headset and stare forlornly out at reality beyond our soap-chapped fingers pressed to the bedroom window. Next time on Unsee The Future, we’ll take a look at how we’ve been technologically planning to deliver better interactions in daily life and contrast this with some very different experiences of reality around us, even before all our interactions had to dramatically change. Has reality always been a bit hijacked – and could this pandemic awaken us from or more deeply enslave us to the Matrix?