Your travel card is still valid.

In episode seven, we opened our initial look at the challenges of city life in the twenty-first century, by acknowledging that not all our grand visions of future urban living have quite worked out, even when they've been inspiringly beautiful. And the mettle of city planning is already being tested with the rise of more and more megacites across our planet – a trend that has tipped us past the point where more of us today are living in the concrete jungle than are not. What can we learn from the language of our place and the images of how we hope to live in the most resource-challenging time in human history. Are there any principles to point us towards something more hopeful than endless poorly-serviced slums, townships and favelas?

As well as right here, you can listen on Soundcloud, Mixcloud or in a search on your favourite podcast app.

As well as right here, you can listen on Soundcloud, Mixcloud or in a search on your favourite podcast app.

VISIONS OF TOMORROW.

What might we learn from our tomorrow stories of the city? One of the biggest, and most cared-for, cinematic future stories of the past few months is the nervously-awaited sequal Bladerunner 90210. Sorry, 2049. We all know the Bladerunner world, from Ridley Scott’s entrancingly envisioned bitter future fairytale, conjoured from Philip K Dick’s original novel. The rain. The neon. The misery. The artful dereliction. The rain. The beautiful deadly robots, as jaded with their fake humanity as all the humans. And Denis Villeneuve was positively reverent to this visual language in his return to this world. And it feels like we can imagine in its viscerality the coming urban future of humankind – a badly evolving artificial mess. But how clearly does it speak to us about now reeeally?

In the Future Cities Project, Doctor HJ McCracken suggests this film is essentially continuing down the ‘fork’ of the original world, and the in-world truths supplant a wider relevance to us in 2018, leaving, as he puts it, little room in its theatre to imprint our current worries. It attempts simply to nod at them. “Pervasive surveillance and the effortless execution of miscreants by remote-controlled pilotless drones (whilst the operator gets a manicure) makes a showing,” he says, “and as a counterbalance we are allowed a marginally hopeful scene involving bees. The Pacific Ocean is kept at bay by an enormous seawall, and weather conditions seem to change faster than you could switch channels on TV… the world-melting disaster presented here drives humanity to desperately invent advanced technologies to survive, but the end result is to merely exaggerate existing power structures” he suggests. The looming dark corporate power. The rain. The lack of rain. The endless miles of tomato cloches.

It doesn’t aim to give us any templates of the urban human future, and we should be careful not to infer them too specifically. The film explores what makes us human; its cityscape is a tonal backdrop to this. To look forward, I’d suggest it’ll help to first look backwards, and meet someone who defied the projections of the future of her own time.

Jane Jacobs. Ever heard of her? Ruddy legend, basically. If you’re a sustainable urbanist hippy, which I seem to be becoming these days. Because she wasn’t just a public realm community visionary, her convictions shaped the heart of modern Manhatten. By saving some of its most thriving, characterful (and now expensive) districts from expressway bulldozers. She came to prominence in the middle of the last century in a very public series of spats with New York City planning tzar Robert Moses, beginning with his plan to run a big road through the middle of Greenwich Village in 1955. He, the embodiment of modern, state-heavy, Knock Down All This Old Shite And Start Again development progress, derided her as ‘just a housewife’ and her cause as “supported by nobody but a bunch of mothers.” It was a different age.

What Jane Jacobs advocated was recognition of the human realities found in successfully thriving communities. And it wasn’t neat zones of different functions and disconnected highways blocking out the sun. It was diversity. Levels of use all at once. She coined the evocative phrase the teeming city and her masterwork, The death and life of great American cities, published as her notoriety spread with her socially-mobilised successes against the massed ranks of corporate interests, has become an urban design cornerstone. Even I have read it.

As Anthony Paletta says in an article for The Guardian: “This broadside against the prevailing scientific rationalism of urban planning extolled diversities of usage, old buildings and the organic structures of cities: “Why have cities not, long since, been identified, understood and treated as problems of organised complexity?” It was a powerful call in an era in which any such complexity was the very thing that planners were looking to organise out of existence.”

, in a very telling personal anecodote, says that she actually got to meet Jane in the early nineties, when giving a lecture on something or other to do with urban planning. Poor sap. Because Jacobs was in the audience, and she was first to put up her hand afterwards:

“The first hand up – sharply so – belonged to this elderly person. How wonderful, I thought, a citizen who has never stopped being engaged. What came out of her mouth, though, was one of the sharpest critiques of my way of analysing the city that I’d ever heard – and probably ever will. She pursued a line of questioning quite different from what I usually get. She continously returned to the issue of “place”, and its importance when considering the implementation of urban policies – notably the loss of neighbourhoods and erasure of local residents’ experiences.”

Place making. It is the core phrase at the heart of why my own wife, the lovely first lady of Momo, goes to work in her job. Somewhere along the progress line of modernity, we lost the fascination and understanding of complexity that makes a city tick – we wanted to neaten it all up. Badge it and park it and contain it. But life doesn’t work that way. As Sassen says, Jane Jacobs: “would ask us to look at the consequences of the sub-economies for the city – for its people, its neighbourhoods, and the visual orders involved. She would ask us to consider all the other economies and spaces impacted by the massive gentrifications of the modern city – not least, the resultant displacements of modest households and profit-making, neighbourhood firms.”

I remember bobbing about in the sea somewhere in southern Italy with Mrs Peach a good decade ago, having just pinched her copy of Great American Cities while on vaykay. There’s something about its calm intonation that is compelling, even in its thoroughness; there is a lot to inspire talking about somehow. And we did. Bathed in glittering holiday sunshine, surrounded by nature, we were obsessing over how streets worked in the urban environment. I don’t know what happened to me when, exactly, but it seems fascinating to me as an obvious implication of architecture.

A key thing that stayed with me from the book is the principle of ‘eyes on streets’. The observation that a community high street works because of the layers of people using the space at the same time. All hours of the day, for many different uses at once. Something that, when it works, does so partly because it plays into the sociological truth of human relationships – that we all need different levels of them. A handful of true family, a ring of good mates, a network of likeable colleagues and gym buddies, a background of recognisable regular faces at the shops. All these positive radiations of connection move around us everywhere we go, with our phone signals, like Match of the day post-goal analyses of the players. And these radiations enmesh and link like a hive. Meaning you can ask the butcher to keep an eye on your bike for a few moments without worry, but without having to attend his son’s bar mitzva either.

Natural surveilance, all hours of the day. And rather more. The poetry of possibilites.

Jacobs puts it evocatively in this extract:

“Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvelous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order. Its essence is intricacy of sidewalk use, bringing with it a constant succession of eyes. This order is all composed of movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we may fancifully call it the art form of the city and liken it to the dance — not to a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse, but to an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole. The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and in any once place is always replete with new improvisations.”

In his article re-appreciating Jacobs’ most famous work, Ned Beauman says the book was a wider hit than you might imagine. “For a rigorous and polemical manual of urban planning, it achieved a remarkably wide readership, perhaps because it’s such a rare joy to read a book about cities written by someone who actually seems to appreciate what makes them fun to live in.”

Well, I mean, talk about authenticity. She walked it. Lived it. Didn’t just stand on the demonstration line, she organised it. And not from some grand culture of protest – from specific conviction. She was officially unqualified – and worse, a woman – who had the temerity to use just her eyes and intelligence and honest feelings to engage with the human environment around her and ask questions about how it worked. What was good for the humans making it up. And she appeared to have no qualms about standing up to very hefty cultural power in New York at the time to do it. And the power of those convictions won – all of Moses’ later schemes for highways were eventually dropped. Try to imagine Manhatten missing Washington Square Park, half of Greenwich and most of Soho and Little Italy. She defended them all in the name of proper street culture.

Now think about the relocation of families in London during the clearance of the slums. The need for new housing was desperate, but the community life in the streets of those prefabs was dismantled and put in separate apartments in highrises. A psychology of living that seemed sinister to some from the gleaming, progressive beginning – JG Ballard’s High Rise imagines the aspirations of the elite turning the compartmentalisation of human life into a grotesque psychosis. The irony of London high rise living may be that by the time the buildings are less than gleaming, they may be starting to function a little more like communities. The Grenfell tower stands to this day as a symbol of community, well, betrayed. By soulless economic separatism.

Now picture your highstreet. If it’s in the UK, there’s a good chance you are picturing something worse than forlorn. Depressing. Empty shops and homeless people. The great out of town retail boxes and the illusion of ‘free parking’ tempting everyone to drive there, rather than catch the bus into town. And that was before the internet threatened retail as we know it.

It is a struggle, even in a comparatively attractive place like my home town, to get people loving their town centres and using them. If people aren’t living there, and served with all the means to truly live there – food, shopping, entertainment, yes, but human scales of walking and permiable routes to get around and plenty of interest at ground level and safe feeling green spaces, integrated nicely into the natural flow of the streets – people will vote with their feet and never show up. What we’re talking about here is really… heritage. Can we feel any potentially life-wedding identity in the form and fabric of where we live, and has it been smartly channeled, amplified and connected to work better in modern times than when the olden days were first built?

It’s a question of ownership. Not simply, who does? But what does it mean. And how do we implement it with sufficient human nowse that we can scale it to the megacity’s great needs, and great opportunities?

SEEING THE HOPEY-CHANGEY BIT.

Door knobs. They matter. The more there are at ground level on a street, the more people are likely to find a reason to hang around and maybe try one. The blocks that have flat office glass to the pavement tend to see people hurrying on as though they don’t belong there. The psychology of the built environment. Humans, eh? Knobs.

Somewhere that has a lot of door knobs is Amsterdam. And it has an awful lot more than that going on at street level. The old city’s layout goes back to the fifteenth century when the canals were first dug and the boom in its trading life blossomed into the characterful leaning townhouses and Dutch-gabled former warehouses, and funny little steps, and cute little bridges, and cheerful potted flowers and puttering glass-topped boats we know as tourists today, more than three hundred years later. It’s beautiful and its inviting. Somewhere you want to just hang out, man. Even with the tourists. And the regular gag of hemp. But if you find yourself wandering around this miracle of drainage management wondering what a little old town apartment here might cost you, it’s likely because it pushes a lot of human brain happy buttons.

Being old, it’s people-scaled, so you can walk it easily. Being flat, you can bike it healthily even more easily – and what looks like trillions of bikes festoon every inch of public space like a mechanical spore explosion as a result. Bike lanes are intrinsic to the rapid flow of connectivity around the city, with an integrated tram, bendy bus, metro and ferry network linking all the environs easily. Trees, water, wonky old buildings, the warm whine of electric public transport, art galleries and modern architecture, gently playful exploration around every corner, cosy coffee shops, funny sculptures, a little urban wildlife, a lively vibe at a sedate pace, people standing in windows in their pants. It’s got all the eurocitybreaklove you could want.

Sure. It could be Brugges. Bits of Berlin. Definitely channeled some Strasbourg here and there. A good dollop of Copenhagen. I dunno. It’s all lovely to me, organised and apparently values-shaped as the whole modern flow of such cities appear. They make me feel good. But are they the future of the city, these heritage-bound seats of old colonial power?

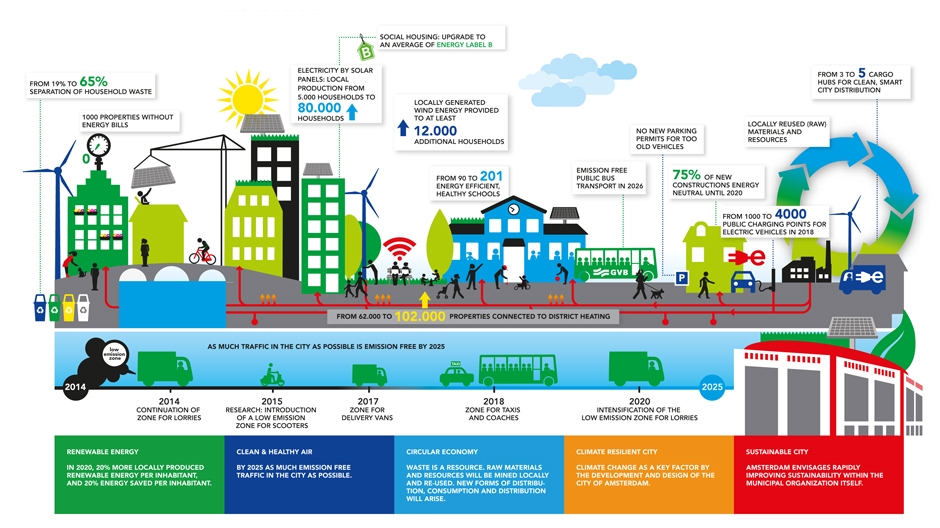

Amsterdam is planning for the future. We went to look at it on a trip last week, tromping through the rain to a building site as we do. Houthaven is essentially a brand new district all going up at once to the north-west of the old horseshoe of the city, which the city planners say will be “100% sustainable”. And they have a pretty integrated take on this, including the wide retconning of old properties up to much more efficient energy standards, the heavy investment in locally-generated clean energy, and the richer implementation of circular economic thinking. All jolly good. Despite the brooding headquarters of Shell staring at it all across the Ij. If they’ve got any sense, they’ll be investing in it.

But Europe’s future city problems aren’t just about the potential of millions more refugees piling up from North Africa in the next decade.

“Every EU Member State has cities that are shrinking within its boundaries. Current estimates suggest that 40% of all European cities with more than 200,000 inhabitants have lost significant parts of their population in recent years and that many smaller towns and cities are also affected”says a report from Hans Schlappa and Uwe Ferber. Population growth is not the only people-numbers problem societies are facing. Rather like the true miniscule percentage of Britain technically concreted over, our view of the world is shaped by the challenges right in front of us personally. It’s not exactly a hopey changey thing so much as a new perspectivey thing – but this is as valuable in shifting how we see the problems around us. They are usually not the single issue frighteners we like to fixate on.

How might the city, at any scaled, get fitter for the future? Plans like the Dam’s surely sound good, at least, and most of our challenges will be about refitting old infrastructure, not sweeping clean and starting again. Especilly if we want to tap into what already works about the heritage of our streets. But it’s worth considering the principles of how to make a city ‘smarter’.

Now don’t roll your eyes. While techheads love to fixate on digital connectivity, not least of which because digital living is essentially changing what it means to be human, but the real future health benefits of any tech will lie how it finds its place in wider human environment – physical, social, emotional. Consultancy Sustainable Amsterdam sites six key elements to measure a city against to place it in the Smart charts: People, governance, environment, economy, mobility and living. As they say: “These elements are used to evaluate a city’s human and social capital, participative democracy, natural resource management, economic competitiveness, transport and quality of life”.

They look for “high levels of social capital, flexibility and tollerance” with a “spirit of innovation” and cultural adaptibility. A good engagement with the local political process and a transparency to warrant it. Decent air quality levels and sustainable energy and waste practices. Great public transport. And “high levels of safety and social cohesion” supported by good access to housing, culture and social services. It all sounds a bit utopian, but such a model banks on the virtuous circle of investing in feel good.

What’s interesting here is that none of these principles are tech-dependent. What the digital can do is amplify and unlock the opportunities they collectively present.

Innovation lab Future Cities Catapult reported back from Smart City Expo World Congress in Barcelona at the end of November with a headline list of recommendations they feel came out of this meeting of future city minds. And to build your smart city will take the usual tough things – strong leadership advocating skills development, collaborative planning and partnerships and keeping an accountable handle on your funding, while trying to build that budgeting into existing statutory frameworks. I know, all the fun just went out of it. Especially if there’s still no city WIFI. But the key thing is engagement – taking the public with you. As Singapore managed to get right in its transformative sustainable water initiative, as we saw in Episode 5.

The technology can help pull together audiences with stories and different partners with accountability. And with a lot of tech impending, having a strategy for integrating it will matter. From vehicle automation, to smart systems upgrading all manner of municiple functions, to telecoms infrastructure, like the 5G rollout or trustable public WIFI, to the massive potentials of augmented reality lighting up the ordinary world around us. Not just with spaceship attacks but helpful live information.

What none of this swish sounding technology will do is fill in the gap of the essential job always at hand: placemaking. All this brilliant stuff is tool – ways to help us go with the human grain much more easily in a modern context. You first have to outline your story before you tell it. And the story to tell has to be something tapping into truth – the heritage of place. Who lives here and how have they shaped it? Amplify that, encourage and adapt that to modern needs, and you’ll find emotional flow. Y’know, people voting for what you’re doing.

When people feel that the place around them knows itself, celebrates itself, that its visible champions recognise what everyone else does there, you have some momentum to surf, I’d suggest. And when people discover at every turn a place that looks like it’s leaders have always gotten there ahead of you, thought of it properly before you need it, it creates a warm fuzzy appreciation. Like writers of favourite scifi franchises really earning the suspended disbelief of their viewers – I don’t need to see the loo in Captain Picard’s ready room but knowing it’s on a deck plan of the Enterprise helps me believe she’s a real ship carry real people leading real lives. In space. City planners build in love for their developments when, behind the scenes, they build it nerdy. And all the flashy special effects are driving the story. Properly connected, and properly recognitional. Respectful.

Not just the immediate interface of an app screen, but the useful information it unglitchily connects you straight to. Not just the modernness of the public space you’re entering, but the readability of it – how lost and uncomfortable you don’t feel. How at home, you do. How safe. How interested. Like every square plate or door handle or window dimension sings from the same more formal architectural design sheet of Charlie Corby’s Radiant City, the function of a modern city’s core amenities and comings and goings should surely feel somehow part of one intention. But without killing the richness of the cultural possibilities with an overtly heavy hand. The teemingness of the city. It doesn’t all have to be neat and tidy, but it does have to be engaging. Urban planning should be planning for the freely complex living of multiple human experiences at once, but they should be helping ordinary folk find simple ways to navigate the essentials of enjoying it. And tech can help many things work together better.

It’s firstly metrics, mate. Data – telling managers just what is being used or accessed at any time, to help efficiently manage the resources, and helping the rest of us know easily where to go to find anything. Helping us see past the chaos or the simply alien as a visitor, and helping us live more smoothly as a resident. Connect. But all this works especially when it’s built on good physical and emotional thinking.

Transport is, in essence, the true lifeblood of a successful city – the easier it is for people to get about its landscape, across all its communities, the healthier its economy seems to be. The less ghettos are likely to remain truly ghettoed. But there is transport and there is transport. And while this is a whole separate episode of Unsee The Future to come, the truth is that the motor car is a brilliant as it is terrible for human living. And this has shown itself in our cityscapes.

It’s likely no coincidence that Jane Jacobs’ movement saved much of Manhatten from the massive ten-lane autoroute dreams of Robert Moses and his culture, and today’s Manhatten has much about it that is richly interesting and working for its inhabitants. Yes, there’s no escaping the historic truth that the city basically went bankrupt in the 70s and gangland violence was a bitter reality in the Bronx and elsewhere as racial inequalities boiled over. I mean, just re-watch Freidkin’s The French Connection. Good lord, that city looks rough. But for all its ups and downs, the not demolishing of much of its heritage has come good in many ways on the other side. Pottering around Hell’s Kitchen today isn’t all superhero gangland punch-ups, it’s coffee shops and Hudson-glimpses and interesting old buildings and The Daily Show studios. And such potterability has been reclaimed successfully elsewhere in the world. Plus, the grim seventies in New York gave us classic hip hop, so culture wins in the end.

Seoul, South Korea, is right up there with the megacities for scale. But in 2003, the city’s mayor, Lee Myung-bak, took the big decision to remove its super highway. As Kamala Rao says in Grist, what the Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project accomplished “— tearing down a busy, elevated freeway, re-daylighting the river that had been buried beneath it, and creating a spectacular downtown green space, all in under two and a half years — is nothing short of amazing, not because it actually worked (there was plenty of evidence from other cities to suggest that it could), but because they were able to get public support for it. It’s the stuff urban planners dream about.” he says.

As Alissa Walker says in Gizmodo: “It seems counterintuitive, right? Rip out eight lanes of freeway through the middle of your metropolis and you’ll be rewarded with not only less traffic, but safer, more efficient cities? But it’s true, and it’s happening in places all over the world.” And she goes on to site schemes in San Fransisco, Portland, Madrid and Seattle that all seem to prove the same point.

“It turns out that when you take out a high-occupancy freeway it doesn’t turn the surface streets into the equivalent of the Autobahn. A theory called “induced demand” proves that if you make streets bigger, more people will use them. When you make them smaller, drivers discover and use other routes, and traffic turns out to be about the same.”

Cars are humanly positive to us as drivers, and humanly negative to us as communities. They’re both personal havens and isolation pods; easy and flexible direct transport and air quality wreckers. But whether I love my little old Audi TDi or not, the practial truth is that the efficient traffic flow of the car through the city usually gets in the way of other forms of getting about. Other more community connecting and bodily healthy means of getting about. But we do need different scales of transport – the future isn’t all bikes or walking. The point is, it isn’t all anything – the successful future city will be shaking down the best grades of transport for the right jobs.

Across Africa, most people today still live in some kind of rural communities, but the rapid urbanisation of the continent’s cities is the big story of the next few years, happeing as it already is. But it’s not simply turning into more township misery. In the Ethiopian captial, Addis Ababa, a rapidly intensifying urban life – in contrast to some of the country’s climate change-challenged rural regions – is leading to some interesting planning developments, including the opening of a new light transit railway connecting across city and a more integrated transport policy emerging. As Julia Bird and Simon Franklin say for the International Growth Centre: “Greater efforts to provide affordable housing, better transport links, and investments in infrastructure around Addis Ababa have shown tremendous promise in helping shaping the city into a more productive, inclusive, and liveable space for the new waves of urban dwellers.” It’s certainly something to watch, I’d suggest.

As FastCompany explored its article looking at the top ten cities of 2013 “leading the way in urban sustainability”, taken from the C40 sustainable megacities organisation, Bogota’s urban transportation, Melbourne’s energy efficient built environment, Copenhagen’s carbon measuring, Mexico city’s air quality improvement, Rio, New York, Tokyo… the big cities of the world have been trying to be seen to develop ways to address human living against the coming challenges. There’s a lot to go find out there about it. And it’s more exciting to think about from a city level point of view than a government one, as they say interestingly.

“Take all of the best qualities of these municipalities – effective road management, cap and trade, sustainable energy, excellent public transportation, a zero waste program, and so on – and you have an urbanist’s dream city. That dream city may not be a reality yet, but the first step to creating one (or many) is learning from cities that already excel in specific areas.” Because, the conclude thoughtfully: “while the United States may have a hard time adapting resilience lessons from Japan, New York City might be much more willing to learn from Tokyo.”

But it’s Tokyo that may be a good final illustration of the possibilities for the future city. It is the largest city on Earth by a good long way and has significant density. So you’d imagine it’s just a mess of polution and ghettos. But it’s not quite that. With the 2020 Olympics looming, the city has had an aim to become dramatically more sustainable and to do so has laid out a pathway to getting there, which is proving to be a useful plan for other cities to learn from. If the daddy megacity of them all can make progress, there is hope and example for the planet.

As Sustainable Business Toolkit reports, Tokyo released its ten-year Climate Change Strategy in 2007 and its aims were to shift the whole expectation of CO2 use in relation to lifestyle, to build greater efficiency of renewables, tap into much smarter use of passive energy around the built environment, to encourage a greener sense of city lifestyle, and to target a ‘carbon minus’ strategy across the board. To do it, they did much to encourage private enterprise and the business community to get stuck into the challenge, while encouraging private homes to face the same awarenesses domestically. And they proposed to get serious about vehicle emitions.

It’s no simple thing at all. Idiosyncracies of culture throw up some interesting results around the world, and here that includes a booming property sector that barely increases housing stock, because of the reportedly rather disposeable view of home design, a likely result of both a playful culture and an earthquake zone. Today, the city has evolved its aims into a new campaign snappily suggesting they want a “New Tokyo – a safe city, a diverse city and a smart city.” They aim, they say, to make the place resilient to disaster and a place that “embraces diversity and is full of kindness and warmth, where everyone can lead vibrant lives and be active in society.” Sustainable, successful and demonstrative.

If Tokyo works at all today, it’s because it is transit-rich. Rail networks across Tokyo-Yokohama are extensive and modern, to say the least. And that sense of pride in achievement and technology is, you better bet, going to take the country forward into the future. Though I’ve yet to wander wide-eyed through the megalopolis myself, I understand it is a gently awesome experience, a sense of something very considered running through it’s rushing arteries everywhere. With a massive challenge still to manage its waste alone, the likely future successes of Japan’s cities can bank on the country’s economic energeticness. This is a productive place, committed to progress. And the Fukushima nuclear reactor disaster has put a huge new emphasis on backing renewable tech development. There’s no runaway success here exactly, it seems, but there’s no runaway disaster either. And in a city of heading towards forty million people, there is a lot to watch about Tokyo.

The great story of our time, when it comes to successes in city living, will be – and are – where innovations combine naturally, and enhance human habits. That’s what our grand architectural visions should be expressing and encouraging, I would suggest.

As Edward Glaeser says in an FT article, Niemeyer’s great, visionary Brasilia has many good human lessons to learn from, in it’s successes and its failures.

“He built using inexpensive, highly durable materials such as reinforced concrete, which helped make height affordable. He was always engaged in a dialogue between past and present and excelled in connecting the short and the tall. And his buildings tend to seem Brazilian even though they are part of an architectural flow that started with Chicago’s skyscrapers and then coursed through Europe. But when we consider the city that success eventually allowed Niemeyer to build, it should also serve as a warning. The modernists were good at designing functional and striking structures, but far weaker at understanding how those structures fit together to form a city. Le Corbusier’s own vision of skyscrapers surrounded by grassy spaces seems utterly ignorant of the streetlife that powers urban interactions. Cities are complicated organisms that thrive when they are messy and filled with mixed uses; the jumble enables people to experience the changing mix of urban marvels.”

What Glaeser says he disagrees with Jane Jacobs about is scale. While she says it is the local high street that works best for humans, he says, Glaeser thinks that the pursuit of that dream in new district developments has lead to urban sprawl and the depowering of density. Something we can’t afford in the cities of the future.

Personally, I think they’re singing from the same hymn sheet, it’s simply that Jacobs’ Greenwich Village in 50s New York looks less dense than the kinds of city developments we should be envisioning for the 21st century – but the principles are core. The green city looks like the future in most people’s minds at the moment, conjouring as the phrase does a general sense of healthy efficiency in urban living. But there is still currently a fly in the ointment, as John W. Day and Charles Hall say in America’s Most Sustainable Cities and Regions: Surviving the 21st-Century Megatrends. It may sometimes be touted that New York is perhaps the greenest city on Earth, when its density and carbon footprint and general fluidity of movement are analysed together, while more rural states in the US have higher CO2 scores, but the truth is the more oil-producing states are producing it largely not for themselves but elsewhere – noteably the resource-hungry cities like New York. Are they so virtuous?

And so perhaps this is where we first arrive at something that will turn out, I suspect, to be utterly transformative to our dialogue with our planet in the coming two decades. The viable switch off of oil and gas for renewables. And with it, a fundamental mindset change. Micro generation – local generation.

The green city will be truly so if it can produce its own fuel for getting about easily, living comfortably and eating healthily. Not simply by producing it in cleaner ways, but facilitating doing so on site. Not transporting power across vast distances from massive single-point generators.

The many solutions, not the few. Encouraged together cleverly.

If there’s one place that’s not been known for it’s green credentials OR its sense of place, it’s Emerate of Dubai. A miracle of money determination, flowering glass, steel and SKIING in the desert of the Gulf, it is, forgive me for saying, a soulless place. It’s not, on the face of it, built on local heritage at all – it’s all so new, and depends so much on oil money to keep its aircon units thrumming. But… it may be in the early process of achieving the turn around of both these dehumanising problems in one falcon swoop.

As Robert Kunzig says in National Geographic, in Dubai: “The temperature outside can get close to 50 (122°F) in summer. The humidity is stifling then, because of the proximity of the sea. Yet it rarely rains; Dubai gets less than four inches a year. There are no permanent rivers. There is next to no soil suitable for growing crops. What kind of human settlement makes sense in such a place?”

What turned this tiny fishing port into a megatropolis supposedly sporting the third busiest aiport in the world that is, even to city soul-seekers like me, undeniably impressive, was oil. But not just oil. Dubai has boomed because it threw open its doors to business and other travel, not just the oil industry. As a result, it caused a property boom that has, in the relentless desert heat, snowballed. It looks at first glance like a place built on confident determination and a certain chutzpah. But I know from my friends and visits to the region that people living in the Gulf are quietly very aware of their place in the oil world, and their almost complete dependency on it. And for them, it’s linked to environmental responsibility as well as sheer economic survival; a number of green initiatives and clean energy projects pepper the countries neighbouring Saudi Arabia and there are many folk who see it positively as the future. Expressed impressively in one concentrated location in Dubai – Sustainable City. No mucking about, we call it that.

Sustainable City has a very telling opening statement on its website when you first land: “Our vision began with a calculated optimism that sustainability is achievable while maintaining all of the societal comforts we have grown accustomed to.” No kidding. If an oil state such as Kuwait can give all its citizens a subsidy just for staying, and offer thousands of well-paid jobs in sprawling municipal departments because of one massive tentpole economic driver, you’d better have a hell of a plan for removing that tentpole, right? Thankfully, Arab communities don’t just know a thing or two about oil and gas technology, or city building and business development. They still know a thing or two about tents.

The site is a community of 500 villas built to achieve carbon neutrality, through a system of PV microgeneration – there is, after all a LOT of sun in that location – and building efficiencies. It is, they claim: “a working model of what the future could look like… a modern application of social, economic and environmental sustainability in the built environment. Achieved through innovative design, stakeholder engagement and future monitoring to sustain itself. The first operational Net Zero Energy city in Dubai, and is modeled to become an international showcase for sustainable living, work, education, and recreation.”

Interestingly, the project doesn’t simply talk about do-ish green energy technology. Up front it says it aims to: “encourage communities to adopt sustainable and healthy lifestyles”. It spells out its conscious aim to face the climate crisis, stating flatly: “The response we must all embrace to this pending adversity is to adopt a lifestyle that accommodates the future. We are at a crux point where the decisions we make now determine the well being of our planet – never have the stakes been so high.” Going on to conclude rousingly that together: “we can broach the frontier of a new era, laying the foundation for generations to come.”

Like all ‘green’ ideas, it sees an inherent integration in all types of wellbeing and success. In one of your charmingly curmugeonly moments you might remind us to be wary of such directive sounding utopianism – more dishonest bloody socialism from trendy toddlepots. Well, keep up the wise circumspection – I do like to get carried away with hopey changey things and I’m more naiively comfortable than most humans on Earth currently, so good point. But I don’t don’t know if you’ve visited a Gulf country. They’re not your typical socialists. And I don’t care about the badge, I’m just interested in whether the approach honestly bloody works for us.

Situated as they are in the baking bleeding heat of Dubai, the homes themselves are all oriented north to get as much shade into the experience of living there as possible, and help reduce aircon energy – backed up by all being coated with UV-reflective paint. Running up the spine of the layout is a series of eleven bio domes, surrounded by meandering water features, trees and other greenery – the farm. Growing all manner of edible produce, its fed and cooled by grey water from the homes, via the fountains and pleasant Hobbiton-esque landscaping that employes some natural bio filtering of the water with papyrus reeds, with the wider planting producing lots of harvestable goods, like dates and pommegranate and papya. They’ve even turned some of the construction materials from phase one into public art.

The site as a whole can produce 10 megawatt-hours of its own energy a day – and 3 of those are from the car parks alone. While much of the thinking in the design of the place aims to be integrated, neat and tidily laid out as it is, the cars are kept deliberately zoned away from the community’s human traffic, parked together cleverly and simply under shades that are all entirely solar panel covered – energy generation that directly feeds all the municipal power needs like street lights and water pumping.

As director of the innovation centre, Karim El-Jisr says: “When you plan sustainably from the beginning – not an afterthought, an afterthought is expensive – when you plan it right from the begining building somewhere like this is no more expensive.”

In talking to part time mechanoid Robert Llewelin on Fully Charged, he goes on to claim that, where the average global citizen today produces more than 7 metric tons of CO2 per year, their own estimates for residents of their community have rather more than halved that. Despite commutes to the rest of the city in gas-guzzling monster cars.

“Every country has its opportunities,” he says, “but we want to be future-ready. That’s what we say. Meaning the climate is changing, things are getting more difficult and we all have this responsibility to bring down our footprints, so we try to personalise both the problems and the solutions.”

Sustainable City looks rather pleasant, in a newy-new kind of way, but then, virtually everything in the Gulf is newy new and a long way from bedded in over generations, and this community has a slightly more cared-for and nature-encouraging sense to its design than the simple glass, polished granite and steel that can predominate elsewhere around the region. The project is, currently, essentially just another isolated endeavour. But such is the nature of early R&D. Test beds. Illustrations of what’s possible. And voices questioning the status quo. Even in a status quo-starched culture like the Middle East. Even… in the heart of oil and gas power. And the voices are being listened to.

It is the smart combinations of things that will facilitate healthier living in growing cities of the future. From AI managing much analysis and driving new more flexible urban transit, filling in public transport gaps more affordably, to AR and playful reachability, to green, local energy and electrification cleaning the air, to vertical farming, street community, green nodes as well as grand parks, the rebalancing of road use to the more grades of human flow and naturally encouraging the health benefits of exercise, to the way tech can help people engage with the very planning system itself, encouraging ownership and political accountability. And this last one is the real activator, and perhaps our biggest cause for hope. Because if all these things aid the teemingness of the city in the 21st century by plugging together, one new technical development will begin to flick the lights on.

The blockchain.

This obscure sounding digital ledger system, touted by arch early adopters and digiwunderkinds as futurism nirvanna, may be the emergent element that will light up all the other new developments in combination. And it is a truly massive opportunity – for economies, communities, professions ..and cities. Because it will promote the very thing cities arguably need above all else to make them work. Engagement.

The way to promote engagement isn’t simply to make something more playfully interactive, as Augmented Reality will certainly bring to a whole new level of life, just on its own, soon. It’s something else psycological –accountability. The disalusionment with community always ends up essentially a political thing – people don’t think the leaders of a community are doing a good job. Listening to people. Perhaps being transparent enough. Opaque working and even the whiff of corruption are criticisms of local governments that are rarely too far away in people’s minds, and regardless of political ideologies, it’s probably most to do with the sheer beaurocracy of government. Who is ever going to wade through even public access PDFs of documentation, especially as they’re likely still written in civil service-ese and stultifyingly hard to understand excitedly if you DID find the right documents. It puts us off. And when we’re miles from knowing who is doing what running our town, we can easily allow in all manner of grumble and suspicion. People are often quickest to moan about “duh caahnsil” and probably parking fees than maybe anything else in humdrum life. Definitely where I live.

Now imagine an open, online system of always, unalterably verifiable data, outside any government or corporate system, built as a transactional chain of ordered records, timestamped by a string of peer-to-peer servers with no editorial middle man. That’s the blockchain. And it doesn’t matter that you and I will need a few goes at digesting ways of understanding what it is before it sinks in. The headline here is that it means the ultimate accountability. To such a degree, those in the know describe it as the second generation internet – the internet of values, not just information.

Why? Because it means you can trace the source of any transaction. No more being in-hoc to solicitors’ mystical searches when you buy a house, for example – the blockchain for any property will, over time, grow to have everything ever recorded about it all linked in one place. Not locked up in separate PDFs on different people’s computers. And this isn’t just a technobabbly new bit of efficiency. It’s going to lead to a post-document world.

Now imagine all council comings and goings, all land registry information, all political decisions, all public information, linked to one block chain for your town centre and built into an augmented reality 3D model. You could find out a complete story for any part of town wherever you were. It sounds just sort of techy, but the human implications are of being less and less easy to hide things, and more and more easy to put knowledges together about, well, anything. When it’s easy to see a more complete picture about something, it’s much easier to start to feel interested. And – oop! there you go – you’re engaged. From simple navigation of a new high street, to finding out key information for an aspect of community development, the blockchain will simply diminish dodgy ducking and diving by people connected to the land and building use of a city, as interest turns to confidence among locals.

Ronan O’Boyle explains in an article in June 2017’s The Planner: “With each transaction, we build up more and more comparables and real-time information” implying that more and more people, a bit like using Wikipedia, will find themselves looking for blockchain threads to find out things and be sure of what they’re finding out. And he sites Dubai, amongst other places, as declaring an intent to get serious about it.

“Smart Dubai recently announced that it wants Dubai to be the first blockchain-powered government in the world by 2020” he says, with the complete conversion of all official documents to blockchain on the cards. “The Dubai governement estimates that blockchain technology could save 25.1 million hours of economic productivity each year, while reducing CO2 emissions.”

You can always bamboozle with big numbers, of course, and there is an interesting thread of thought out there that the blockchain is currently not very green, as it takes so many more servers humming away around the world to verify all the data. But that’s not the point here – regardless of how soon we improve the green energy to and the power efficiency of every computer core on Earth, the blockchain is going to revolutionise how handle everything we know – ultimately not just making everything easier to find, but crucially to cross connect. And so, inevitably – and profoundly – to stimulate human engagement with the issues around them more.

And with engagement comes ownership.

Ownership. That’s belief. In not just institutions, or even cities – but people. It will help us know who is on the other end of a decision in our community. Or of anything. Just when the world’s connected crises are demanding one thing above all from us – taking increased personal responsibility. Easily accessible data, to new levels of understanding, will simply enable us to do this. And it won’t be techheads doing it, it will be ordinary schmos like you and me – and that is where technology is going to turn out to be the genius keystone in our bridge to the future. The foundations have to be in the heritage of who we are, but the final connection to a whole new side of the river will be the new emotional responses unlocked by the real potential of a digitally networked human being.

Because, above all, it may be about representation. Everyone – everyone – has to see something of themselves recognised in where they live. And when none of us can hide in disconnected ghettos, either feeling powerless to challenge what happens behind closed doors or able to get away with feathering our own prejudices… well, we unlock the potential of the great human hive computer. Don’t we? A truly living organism – the sustainable future city. As dense in possibilities as people. As rich in understanding as engagement. A place shaped much more by everyone who makes it up.

I’ve swan-dived off the hopey-changey highboard here, haven’t I.

Good intentions or idle daydreams don’t spirit away human suffering. But if the implication of the gathering stormclouds of combining crisis today is that we are all simply going to have to wake up much more and take much more responsibility for our awareness of how everything fits together… we’ll all simply be looking for ways to make sense of and interact with those fearsome challenges. To survive. And we’ll likely find ourselves reaching for these new tools and getting on with it. My growing conviction, from the quiet instinct that was the original purpose of Unsee The Future, is that the more we can individually, as ordinary nobodies, grasp how all this fits together – true human mental wellness with economic story with environmental challenge with technological opportunity – the simply more excited more of us will get. Even if waking up may be like waking up from addiction or an operation – painful, at first.

What eases the pain for every human, no matter what it is, I think is finding one’s place. A place to fit. In the modern world, this doesn’t have to be one geography. But the truth is, once we’ve made place in our mind – with who we are – it will affect where we live. And absolutely should. Because, as we all do this, the change combines and amplifies. And may even begin to see the world around us resemble the one we truly began to believe in, in our heads.

As Saskia Lassen says when thinking of Jane Jacobs’ view: “Why is it so important to recover the sense of place, and production, in our analyses of the global economy, particularly as these are constituted in major cities? Because they allow us to see the multiplicity of economies and working cultures in which regional, national and global economies are embedded. But Jacobs went much further than this. What she showed us, crucially, is that urban space is the key building block of these economies. She understood it is the weaving of multiple strands that makes the city so much more than the sum of its residents, or its grand buildings, or its corporate economy.”

I remember, without any of the pertinent details of names and places and times, a story that has stuck in my mind for years. Of a man searching for a new level of understanding in his religious beliefs. A Christian writer, I think, who had looked up to some great zealous speaker in his own younger years as a source of great Godly inspiration and zappy snappy displays of hopey-changey spiritual certainty. So he tracked him down years later and more or less doorstepped him, I think. Found him in a very unglamourous little town in middle American, far from the big city lights and from book tours and speaking engagements. There he was, kind of just running a little farmstead or something. The searching man asked him: “After all your years of exploration, what’s your one bit of advice to me?”

The other bloke looked at him and said: “Find some place and settle down.”

Wish I could remember who it was. But it’s a story not about rural living versus metropolitan life; it’s not a yearning for simpler times, looking backwards. It’s not even about never traveling or mixing it up. It’s about being fully where you are. And that is what builds a community, wherever you are. Living like that means you are never just a number in a crowd. And neither is anyone else around you. Even when there are forty million of you.

Successful human city life, I’ve come to think, richly reflects successful biological life. Lots of motion, lots of mixing, lots of unforseen possibilities from the absence of stagnant separation. The more local individuals see themselves in where they live – the more we each feel recognised in the system of our city – the more we will own where we live, and so shape it. Helping together to work out the right mix of clever solutions to grow with the grain of where we live. Eating away at the impossible-seeming problems. Sharing the spaces. Sharing the placemaking. Feeling like co-architects in the quality of our lives.

The future will be saved, built and about the many, not the few.

WATCH THE TRAILER FOR A MARVELOUS ORDER

An actual musical about Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses:

CHINA’S ECO-CITIES:

Sustainable urban living in Tianjin >

WHICH TRAFFIC POLICIES WORK BEST FOR MEGACITIES?

Rema Hanna writes for Project Syndicate >

BLOCKCHAIN PLATFORMS CAN ENABLE GOOD WORK

Andy Spence writes for the RSA >

IN DEFENCE OF LOITERING

Emily Badger writes for Citylab >

100 RESILIANT CITIES

Discover some high-level ideas for the future city >